Bach, Mendelssohn, Tullis and More!

We’re back! Come and listen at our new home at Birchman Baptist Church. The concert starts at 6:30 pm, and we can’t wait to see you all there.

Let us know you’re coming on the event page – it’s free and not required, but we’d love to know who’s coming.

Soloist | Violin Concerto in A Minor by J.S. Bach

From the FWSO website:

From the FWSO website:

Eugene Cherkasov has been a member of the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra for over 20 years. He was born and trained in Baku, USSR, and started his career after winning a National Competition at the age of eighteen. He first received international acclaim after performing as a soloist and first violinist with the Quartet of Modern Music at the Frankfurt Feste-89 and at Beethovenhaus in Bonn, Germany. At that time he traveled extensively promoting new composers for wide audiences throughout the USSR and abroad. He later served as the concertmaster of several orchestras in Moscow. In 1990 Eugene and his family moved to Mexico, where he performed with the Mexico State Orchestra. Winning the position of first violinist with the Thouvenel String Quartet brought him to the United States in 1991. Eugene has served as concertmaster and appeared as a soloist with numerous orchestras in Texas. He has also performed in festivals in Michigan, Colorado, Texas, Washington, Vermont, Canada, and Germany, was a faculty member of the Wintergreen Festival in Virginia. Over the past ten years, Eugene has participated in various summer festivals in Italy, including Geminiani and Nei Suoni dei Luoghi, where he performed violin-piano recitals with his wife, Larissa. In 2004 Eugene was a soloist with the renowned Ensemble Archi Della Scala di Milano, performing Bach and Haydn concertos in France.

Eugene graduated with honors from the Baku State Conservatory with a Master’s Degree in Violin Performance and Pedagogy. He also obtains an Artistic Diploma and a Doctorate from the Moscow State Conservatory, where he studied with professor S. Kravchenko. Currently, Eugene is the Assistant Concertmaster of the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra and dedicates much of his time to teaching and performing chamber music.

Concert Program

Though his reputation as a master keyboardist has come down to us across the centuries, Bach was also an accomplished violinist. The unaccompanied sonatas and partitas he composed for the instrument are a bedrock of the violin literature. His son Carl Philipp Emanuel reported, “He completely understood the possibilities of all stringed instruments.” Bach’s own violin was built by the German luthier Jacob Stainer, whose handiworks were more prized than the violins of Antonio Stradivari during their lifetimes.

Though his reputation as a master keyboardist has come down to us across the centuries, Bach was also an accomplished violinist. The unaccompanied sonatas and partitas he composed for the instrument are a bedrock of the violin literature. His son Carl Philipp Emanuel reported, “He completely understood the possibilities of all stringed instruments.” Bach’s own violin was built by the German luthier Jacob Stainer, whose handiworks were more prized than the violins of Antonio Stradivari during their lifetimes.

Almost nothing is known about the origin of Bach’s A minor violin concerto. The earliest parts date from his time as kapellmeister in the churches of Leipzig after 1729. He may have composed it during his appointment to the Duke of Anhalt-Cöthen’s court orchestra from 1717 to 1723. During those years, he also led the local collegium musicum – a group of amateurs and university players much like our FWCO! – that made music on Friday nights at Leipzig’s Café Zimmermann. He arranged this and his E minor violin concerto as harpsichord concertos for the collegium, and they continue to be played in those versions today.

The first two dozen measures, played by the soloist and the orchestra, is a ritornello or “refrain” that recurs throughout the first movement in full and in fragments. These interjections alternate with solo passages that, in Bach’s concertos, are based on pieces of the ritornello to create a unifying melodic structure. The second movement’s gently insistent bass line – nudged along by cellos and basses – is the earworm that steals the show while the violin offers disconsolate, ornamental commentary. The energetic finale is driven by relentless triplets to a gigue that’s more of an angry release than a spirited dance.

Outside the German-speaking world, few of us have read Goethe, either in translation or the original language.  But his colossal stature in the Romantic literature still echoes in the music he inspired: Beethoven’s Egmont, Schubert’s Erlkönig and Gretchen at the Spinning Wheel, the operas Werther by Massenet and Mignon by Thomas, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice by Dukas, not to mention epic settings of Faust by Gounod, Boito, Mahler, and Berlioz. However, the rousing little Hungarian March that ends Part I of Hector Berlioz’ The Damnation of Faust wouldn’t count as one of them.

But his colossal stature in the Romantic literature still echoes in the music he inspired: Beethoven’s Egmont, Schubert’s Erlkönig and Gretchen at the Spinning Wheel, the operas Werther by Massenet and Mignon by Thomas, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice by Dukas, not to mention epic settings of Faust by Gounod, Boito, Mahler, and Berlioz. However, the rousing little Hungarian March that ends Part I of Hector Berlioz’ The Damnation of Faust wouldn’t count as one of them.

In fact, there’s nothing in Goethe’s Faust about Hungary or a Hungarian army that’s featured so prominently in Berlioz’ musical drama. The composer’s only reason for setting the action there was to give himself a reason to insert a crowd-pleasing march:

I took the liberty of bringing my hero to Hungary at the start of the action, as he witnesses a Hungarian army marching across the plain where he wanders lost in his dreams. A German critic found it very odd that I made Faust travel to such a place. I do not see why I should not have done so, and I would not have had the slightest hesitation in taking him anywhere else, had this benefited my score in any way.

Berlioz began sketching Faust while on a concert tour through Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, and Silesia in 1846. Before leaving for Hungary, a Viennese friend advised him that “if you want to please the Hungarians, write a piece on one of their national themes.” Taking the hint, he wrote a march based on a popular Hungarian song about the 18th-century patriot Ferenc Rákóczy. The Rákóczy March was composed in a single night and premiered in Pesth (the future Budapest) to a cheering audience. It was so wildly successful, Berlioz played it in every city on his tour and eventually shoehorned it into his Faust. His memoir of the first performance not only describes the audience reaction vividly but offers a road map to the piece:

On the day of the concert, I felt, all the same, a certain tightening of the throat when the time came to produce this devil of a piece. After a trumpet flourish based on the opening bars of the theme, the march appears, as you recall, played piano by flutes and clarinets with a pizzicato accompaniment on the strings. The audience stayed quiet and silent at this unexpected opening. But when, over a long crescendo, fragments of the theme reappeared in a fugato, punctuated by muffled notes on the bass drum simulating distant cannon-fire, the hall began to seethe with an indescribable sound, and when the orchestra erupted in a furious mêlée and hurled forth the long-contained fortissimo, shouts and stamping such as I had never heard shook the hall… Thank goodness I had placed (it) at the end of the concert as anything one might have wanted to play after would have been lost.

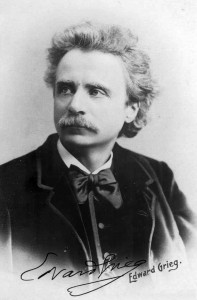

In spite of his classical training at the Leipzig Conservatory – studying the music of Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Schumann – Grieg never warmed to the German symphonic tradition. He did, on a challenge from Danish composer Niels Gade, compose a Symphony in C minor at age 20 but suppressed it the rest of his life. At his musical core, he was a miniaturist who expressed a nativist Norwegian life force in his overflowing collection of Lyric Pieces, his incidental music to Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, and his melodramatic Piano Concerto.

Mendelssohn, and Schumann – Grieg never warmed to the German symphonic tradition. He did, on a challenge from Danish composer Niels Gade, compose a Symphony in C minor at age 20 but suppressed it the rest of his life. At his musical core, he was a miniaturist who expressed a nativist Norwegian life force in his overflowing collection of Lyric Pieces, his incidental music to Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, and his melodramatic Piano Concerto.

The nearest that Grieg ever came to writing anything on a monumental symphonic scale in his mature output were the Four Norwegian Dances in 1881 and this set of Symphonic Dances he composed 16 years later. Both works were based on native tunes collected by the musical folklorist Ludvig Lindeman (1812-1887), who published 600 of them in two editions of Norwegian Mountain Melodies. Grieg’s orchestration style here is big and opulent – with a deep fondness for the oboe in its loveliest melodic lines – but the structure of every movement is a simple A-B-A form, a principal melody paired with a contrasting middle section.

The first two movements are based on halling dances of southern Norway. This is usually an energetic men’s dance full of leaping and kicking. The second movement, though, is a gently wistful tune – in Lindeman’s collection, Hestebyttaren (The Horse Dealer) – with a playfully coy middle section. The third movement is a spritely couple’s dance, a so-called Spring Dance characteristic of the east country near the Swedish border. The finale is a comic pairing of two folk tunes: Saag du nokke Kjoeringa mi? (Have you seen my wife?) in brutalist style set against a charming Brulaatten (Bridal March). True to form, Grieg brings it all to a breathless finish with extreme economy and no development.

Beloved by Queen Victoria, Mendelssohn’s War March was once a fixture at graduations and other ceremonial  occasions that called for stirring processionals ranked somewhere behind Elgar’s Pomp & Circumstance and the Triumphal March from Aida. Combining the inspiration of stately march and upbeat fanfare, Mendelssohn composed it for the incidental music to Athalia, a commission from King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia for a performance of Jean Racine’s 1691 Biblical play. Handel had also used the play as a basis for an early oratorio 110 years before Mendelssohn.

occasions that called for stirring processionals ranked somewhere behind Elgar’s Pomp & Circumstance and the Triumphal March from Aida. Combining the inspiration of stately march and upbeat fanfare, Mendelssohn composed it for the incidental music to Athalia, a commission from King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia for a performance of Jean Racine’s 1691 Biblical play. Handel had also used the play as a basis for an early oratorio 110 years before Mendelssohn.

Athalia – daughter of King Ahab and Queen Jezebel – is the apostate queen of Judah, who rejects the worship of Jehovah in favor of Baal. To secure the throne, she’s had all the heirs of King David murdered except for the infant Joas. Unbeknown to the queen, he’s been hidden away by his aunt Josabeth and her husband Joad, High Priest of the Jews. They wait six years to publicly crown the boy on the steps of the Temple, then barricade themselves inside to await Athalia and her followers. When she and her army burst in, they find the boy seated on the throne and the soldiers frantically disperse. Athalia gives in to her fate and is executed by the High Priest.

Mendelssohn wrote an overture, six choruses with vocal soloists, and the War March of the Priests in 1843-45, the last theatrical project he completed for Friedrich Wilhelm. Prior to Athalia¸ he had composed the music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Oedipus at Colonus as music director of the recently established King’s Academy of the Arts in Berlin. When he declined to take on the music for Aeschylus’ Orestia trilogy, his relations with the king cooled appreciably, and Mendelssohn retreated to Leipzig where he was director of the Gewanthaus Orchestra and the Conservatory he founded.

Renewal Overture has three themes that characterize its optimistic approach to restarting musical life after the interruption that was the year 2020. The trombones open the overture with the first theme, a martial, urgent melody taken up by winds and muted brass. The strings follow with a lilting melody full of anticipation and hints of triumph echoed in the brass. A piano, percussion, and winds interlude leads to the third theme, a lighthearted motif in the oboes which is derived from the opening notes of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, “Resurrection,” but in reverse. The overture ends with a triumphant brass fanfare on the first theme and a bright and hopeful resolution.

Joseph Tullis is a seventeen-year-old violinist and a junior at Paschal High School. He wrote Renewal Overture while attending school online during the pandemic. With his usual rehearsals and performances at a full stop, he had extra time to learn the art of orchestration. His compositions in progress include a violin concerto and a four-movement symphony. He has studied violin for fourteen years, the last three with Dr. Kurt Sprenger.