The Dana Suesse Project

Dana Suesse arrived on Tin Pan Alley in her teens and turned out a string of hits that included You Oughta Be In Pictures, Yours For A Song and My Silent Love. Like her friend, George Gershwin, she also wrote larger compositions that straddled the worlds of jazz and classical. In 1932, Paul Whiteman commissioned her Concerto In Three Rhythms for his “Fourth Experiment in Modern Music” when Dana was just 22. The New Yorker magazine called her “The Girl Gershwin” in the hype of the day.

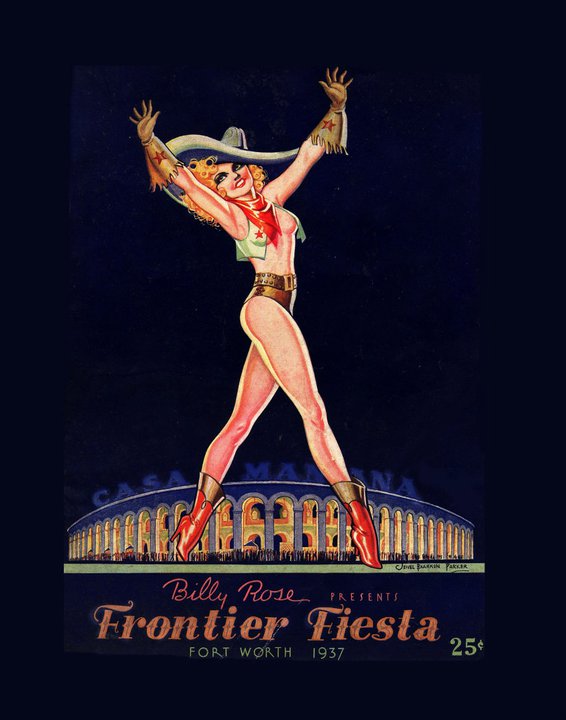

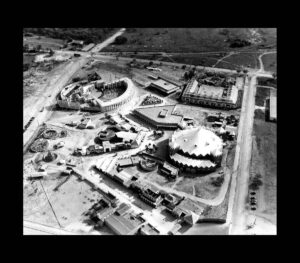

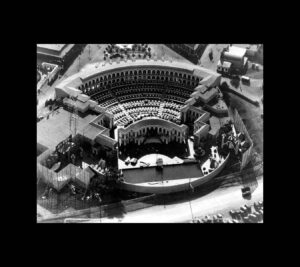

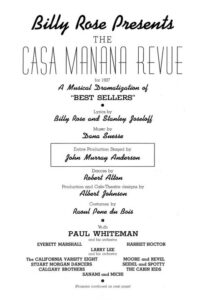

Dana Suesse came to Fort Worth in 1936 to do the music for a show called Casa Mañana. The city of Dallas had been named the official site of the 1937 Texas Centennial celebration, and not to be undone, Amon Carter hired Broadway producer Billy Rose to mount a bigger Fort Worth Frontier Centennial Fiesta. The city spent $3 million on a new dinner theater built to seat 4,000. It held the largest rotating stage in the world, surrounded by a moat that shot jets of water high into the air. The city spent another $750,000 on the production itself, hiring hundreds of locals for the dance numbers. From New York, Rose summoned Paul Whiteman, dancer Sally Rand, director John Murray Anderson and Dana Suesse to put on a show that was talked about for decades.

Fort Worth Civic Orchestra is proud to re-introduce the music and the story of Dana Suesse to our community. She was a musical pioneer who came to Fort Worth at an important moment in the city’s history.

Dana Suesse (née Nadine Dana Suess) was born into a lively era in music and entertainment in Kansas City, Missouri, on December 3, 1909. She demonstrated an early affinity for music, dance and poetry. When young Dana grew too tall for ballet, piano lessons were begun with Kansas City teacher Gertrude Concannon. As a child, she toured the Midwest vaudeville circuits in an act centered on dancing and piano playing. During the recital, she would ask the audience for a theme and then weave it into something of her own. Her first solo piano recital was in Drexel Hall, Kansas City on June 29, 1919. The seeds of orchestration may have been planted during her year of organ studies with Hans Feil, who presented Dana in an organ recital on December 17, 1922.

Dana had great affection for the southern side of her family. As a child she visited them regularly and frequently volunteered Shreveport, Louisiana, as her birthplace. She told one interviewer she was born in Alabama. While she claimed to detest the life of a child prodigy, all through her early career she subtracted a couple of years from her real age, and to the end of her life, there was always some confusion in the public record over whether she was born in 1909 or 1911.

Upon graduation from high school in 1926, she turned down a scholarship from the Chicago Conservatory and moved to New York with her mother Nina. There, she advanced her studies with Alexander Siloti, one of Franz Liszt’s last surviving pupils and a teacher of Rachmaninoff. She also studied composition under Rubin Goldmark, one of George Gershwin’s teachers. She aspired to compose musical works in classical style, but her early writing efforts were rejected by publishers. In New York, Dana began experimenting with jazz styles. She told an interviewer, “I just kept my ears open and began to understand that there was something very interesting called jazz and popular music. This was an unknown territory to me…I compromised and used my classical training to make a bridge between [classical] and what was new to me.”

Her composition Syncopated Love Song bridged that gap between “serious” and “jazz” forms. She wrote it in 1928 and showed it to Nathaniel Shilkret, who recognized a new work with spark and sophistication. Among its novel touches was the main melody, which placed six beats to a 4/4 bar. Taking a one-third cut as co-composer, Shilkret recorded it as an instrumental in 1929, six weeks after the stock market crash, and Dana’s career path was set. The doors of Tin Pan Alley, previously closed to her, began to open up. Publisher Henry Spitzer of Harms Music suggested that the tune could be transformed into a hit song. Leo Robin added a lyric, and Dana’s jazz-classical “bridge” work became Have You Forgotten.

Dana began mining other of her early compositions for their song potential. She teamed with lyricist Edward Heyman to write two more hits, Ho Hum (recorded by Bing Crosby in 1931) and My Silent Love. The latter had also started as a purely instrumental work she called Jazz Nocturne, but the central section lent itself nicely to a popular ballad. Nat Shilkret’s 1932 Victor recording of Jazz Nocturne got the attention of bandleader Paul Whiteman, whose 1924 “Experiment In Modern Music” introduced Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. Henry Spitzer suggested to Dana that she compose a concert work for Whiteman’s upcoming Fourth “Experiment.” Like Gershwin and his Rhapsody, she had no time to lose. In ten days, she hammered out a fully formed composition – in her case, an entire piano concerto in three movements. She took the manuscript to Chicago to show Whiteman and his arranger Ferde Grofé, and they accepted it. As with Gershwin’s Rhapsody, Grofé would do the arrangement. Her Concerto in Three Rhythms owed some obvious debts to Gershwin’s Concerto in F, but it was a brilliant statement from a 22-year-old aspiring composer, and Dana performed it with Whiteman’s band at Carnegie Hall on November 4, 1932.

The next year, The New Yorker magazine called her “the Girl Gershwin,” and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette would tag her the “Louisiana Liszt.” Like Gershwin, she had proved that she could move easily from “serious” concert pieces to popular ballads and was an excellent pianist as well as composer. Her orchestral works Symphonic Waltzes (1933) and Blue Moonlight (1934) followed. She wrote her most famous song in 1934 on a dare. She and Heyman had boasted to Spitzer that they could write a hit song in 15 minutes. “We were just kids,” she later recalled. “Very smart-alecky.” Spitzer pointed to a piano and locked them in a room for a half hour. “You come out with a hit song,” he told them. Heyman lighted on a title right away, the popular expression, “You Oughta Be in Pictures.” In a couple of minutes, Dana had a seven-syllable melody for the title lyric, which she later admitted to lifting from Riccardo Drigo’s Serenade. “I said to myself, I’ll steal it because I know it’s ‘sure fire.’ I knew it couldn’t miss because it had been a classic for years, and the rest of it will be mine.” Heyman came up with the rest of the lyrics in 12 minutes, and they walked out of the room with You Oughta Be in Pictures, which quickly became a hit and a Hollywood anthem.

Dana also contributed songs to the Ziegfeld Follies (1934), Earl Carroll Vanities (1935), The Red Cat (1934) and the score to the film, Sweet Surrender (Universal, 1935). Throughout the 1930s, she wrote numerous popular songs, including This Changing World and Yours for a Song, the latter written with lyricist and theater producer Billy Rose. Dana contributed to all of Rose’s spectacular revues, beginning with a show that took her deep in the heart of Texas in 1936.

[from Peter Mintun’s biography of Dana Suesse]

After having lunch in Manhattan, Dana and her mother finished packing their trunks. They boarded the six-o’clock train for Fort Worth on Saturday, April 25, 1936. The next afternoon they stepped off the train in Texas and were driven to the Worth Hotel, where the Suesses checked into the largest room on the top floor. Dana called for a piano and set to work on the impressive assignment. She would be writing music for Broadway dancer Ann Pennington (prominent in George White’s Scandals of the 1920s) and the stentorian baritone Everett Marshall. Marshall was well known on Broadway, but his rather rigid screen personality prevented him from making a favorable impression in films. The spectacular Casa Mañana show would need big voices, and Marshall had one.

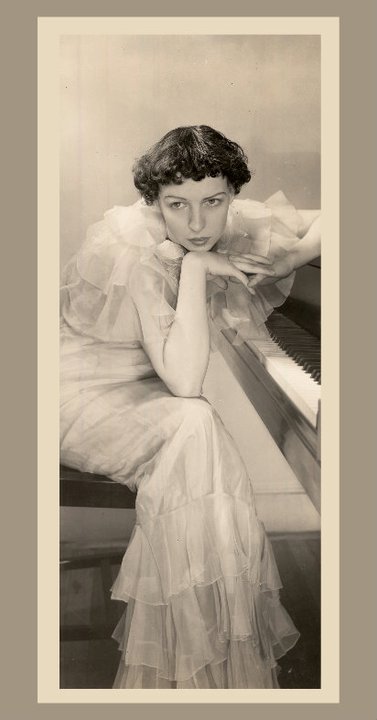

“Dana Suesse is a fragile blonde type with beautiful auburn hair, which frames a refined face…ever so lovely herself, much lovelier than her photographs, for her personality is not the kind that goes across the lens of a camera. The day I talked with her, she wore a softly draped Nile green chiffon hostess robe with a gold leaf belt…her success has been meteoric… She is now looked upon as the most successful woman composer in this country” (Edith Alderman Guedry, Fort Worth Press). In a letter to me, dated September 7, 1973 Suesse wrote, “Not having ever liked the designation of ‘woman composer’…one is either a composer or not, regardless of gender.”

When Dana wanted to get away from the spotlight in Fort Worth, she could visit her cousin, Mrs. R.M. (“Jo”) Quigley. Dana was so charmed by southern hospitality, she often told reporters her birthplace was Shreveport. In truth, she spent many summers in Shreveport, La. and in Texas, visiting her southern relatives. It was easy for Dana to lie about her birthplace; her mother had been lying about Dana’s age since she was a child vaudeville performer. Dana and her mother’s accounts of her age tended to ignore from two to five years. Dana stayed in Fort Worth, working on the shows for three months. She also got a good vacation out of the job, returning to Manhattan only to fulfill appearance obligations.

A four-thousand seat outdoor nightclub, Casa Mañana was constructed on thirty-five acres of desolate prairie on the edge of town (just off University Drive near West Lancaster). The revolving stage was the largest in the world and in front of it was a lagoon 175 feet wide, where handsome young men propelled gondolas in front of the stage. Billy Rose’s press release said that the lagoon contained 617,000 gallons of water, and that the stage was three times larger than that of Radio City Music Hall.

About Billy Rose, Dana later confided, “He always learned a lot from other people, and he trusted me. He was always picking people’s brains. If there was a word he heard for the first time, he would make a mental note of it and use it later. During an early rehearsal, she was sitting next to Rose listening to the new orchestrations for the show. “We were having the first orchestra ‘reading’ and Billy asked me what I thought of the first arrangement we heard. I didn’t think it was very interesting… and he asked me what was wrong with it. I told him it seemed a little pedestrian to me. Well, he apparently had never heard the word used in just this way before. He paused for a minute and I could hear the wheels turning in his head. He got up and he walked over to the orchestra leader and told him ‘Scrap that, it’s pedestrian’.”

The Fort Worth Frontier Centennial opened officially on July 18, 1936. President Franklin Roosevelt pushed a button on his yacht off the coast of Maine that sent an electrical impulse to Fort Worth that cut a lariat stretched across Sunset Trail.

The original music by Suesse was highly effective. Paul Whiteman’s youngest singer, Durelle Alexander, recalled with fondness that when the number “You’re Like a Toy Balloon” ended, hundreds of hidden balloons were set free into the night sky. This was Durelle’s nightly cue to meet her fiancé, Edmund Van Zandt (the son of Paul Whiteman’s Texas landlord). They were wed four years later. Ramona, the popular singer (who went by one name) also found romance in form of one of Whiteman’s many arrangers, Ken Hopkins. They also married after the Centennial was over.

The impressive Whiteman organization was in full attendance. His featured pianist-vocalist Ramona painted the Texas town with fellow musicians Roy Bargy, Frank Trumbauer, Matty Malneck, Ken Darby, Bob Lawrence, Charlie and Jack Teagarden, Bill Rank, Johnny Hauser, Charlie Strickfadden and Mike Pingatore.

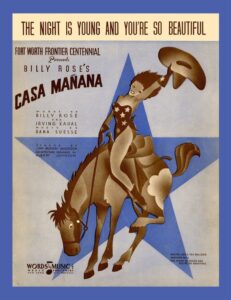

The surprise for all concerned was the immediate popularity of the song The Night Is Young And You’re So Beautiful. The song was introduced at the end of a long scene involving hundreds of chorus girls, boys, singers and dancers. The setting was The Saint Louis World’s Fair of 1904, beginning with such chestnuts as Meet Me In St. Louis, Louis, St. Louis Blues, In The Good Old Summertime, Oh, You Beautiful Doll, The Daisy Bell Song, Why Do They Call Me A Gibson Girl, Frankie and Johnnie, There’ll Be A Hot Time In The Old Town Tonight, and finally, Egyptianna (music by Howard Godwin) danced by Ann Pennington. The final song of this huge, nostalgic scene was The Night Is Young And You’re So Beautiful, sung by Everett Marshall, appearing with Faye Cotton (Miss Texas), dancer Garth Joplin and The Casa Mañana Dancers.

The next scene was The Paris Fair of 1925, followed by Chicago’s Century of Progress Fair of 1933, in which three women sang It Happened In Chicago. In the same scene was the original song You’re Like A Toy Balloon, sung by The Californians with Faye Cotton. Sally Rand ended the scene with her unique nude bubble dance, billed as a Ballet Divertissement. Scene four, The Fort Worth Frontier Centennial Celebration, began with Everett Marshall singing Another Mile, followed by a Comanche Indian tableau, A Masque of Texas, and a historical tableau about which all led up to the 1936 Centennial theme. This was followed by Marshall singing Lone Star with The Californians, and Ann Pennington as The Girl In The Hundred Gallon Hat.

A newspaper account said: “They came from all over to watch Everett Marshall stand on the world’s biggest revolving stage and let 336 rollers turn him toward his singing co-star Faye Cotton, Texas Sweetheart… radiant in a five-thousand dollar gold mesh gown. In that long, hot summer before air conditioning, people sitting on their porches in Arlington Heights could clearly hear Marshall’s vibrant The Night Is Young And You’re So Beautiful being carried to them on the breezes” (Elston Brooks, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 1986). Every evening when it was over, the Whiteman orchestra would re-group and the enormous stage became a dance floor.

Dana’s three months in Fort Worth were an eyeful. In 1973 she told me, “We not only had the Casa Mañana, we had the Pioneer Palace for which I wrote several songs which were never published: The Man With The Handle Bar Mustache and The Lady Known As Lulu. This was a real rough, tough pioneer kind of show, with the stage above the bar. There were so many innovations in this whole Fort Worth show, yet it wasn’t publicized back east. Everybody there though it was some kind of strawberry festival that the Texans were putting on. As a matter of fact it was one of the greatest shows ever put on in America. It really was fantastic. Then we had the third show called The Last Frontier, and they built an entire mountain for it. They made it out of some landfill and rocks and cement… bulldozed it all together and made it look like natural formations. Then Billy engaged three tribes of Indians and a whole herd of buffalo. There was a square dance done by a hundred and twenty riders on horseback. You never saw anything like it. It was wonderful. The opening night of the first Casa Mañana, I had never seen anything like this audience. It was so thrilling they practically tore up the tables and their chairs. And they yelled and they screamed. It was fantastic.” The Night Is Young And You’re So Beautiful was considered the theme song of the Texas Centennial, and the song won the number five place on Your Hit Parade on the broadcast of February 6, 1937 and stayed on the program for six weeks.

Dana was not asked to compose music for fan-dancer Sally Rand. Sally, who had gained overnight fame at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, brought her own music, the Adagio of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, Debussy’s Clair de Lune, and other appropriate music. Her dance was in a revue called Chicago Century of Progress, which opened with the burlesque-style It Happened In Chicago. Sally Rand’s own segment was subtitled Ballet Divertissement, in which she performed her almost-nude fan dance with the Corps de Ballet on the huge Casa Mañana stage. When there was no breeze, she could also do her bubble dance. Billy Rose had a press agent, Ned Alvord, who laid down a policy for the press regarding Sally Rand’s Nude Ranch: No photographs allowed of Sally Rand wearing clothes. He prided himself with the line “Nobody is to shoot Miss Rand until they see the white of her thighs.”

Writer Jack Gordon of the Star-Telegram reminisced in 1986, “Casa Mañana was a magnificent amphitheater rimmed with blue and white arches. Riding high over the theatre’s open top was Texas’ brightest moon, mesmerizing the four-thousand spectators almost as much as the magic Billy Rose provided on his… revolving stage, one-hundred-thirty feet in diameter… nothing delighted audiences more than the show’s extraordinary chorus line. The line of more than forty beautiful women, most of them recruited in Fort Worth, was a dance spectacle that perhaps topped even the Rockettes. For his Wild West show, The Last Frontier, Rose brought down real Indians from their reservations. The Indians, many in paint, lived in teepees on the show grounds.”

After the opening weekend of Casa Mañana, Dana left Texas for New York, where she resumed her routine of radio appearances, concerts, parties at Mary Brown’s, lunches with Eddie Heyman and more work on her symphonic ideas. Her friend, Tamara Geva was now starring in a highly successful Rodgers & Hart show, On Your Toes, in which she played (of course) the ballerina. Her ballet Slaughter On Tenth Avenue was danced with Ray Bolger and choreographed by Geva’s first husband, George Balanchine.

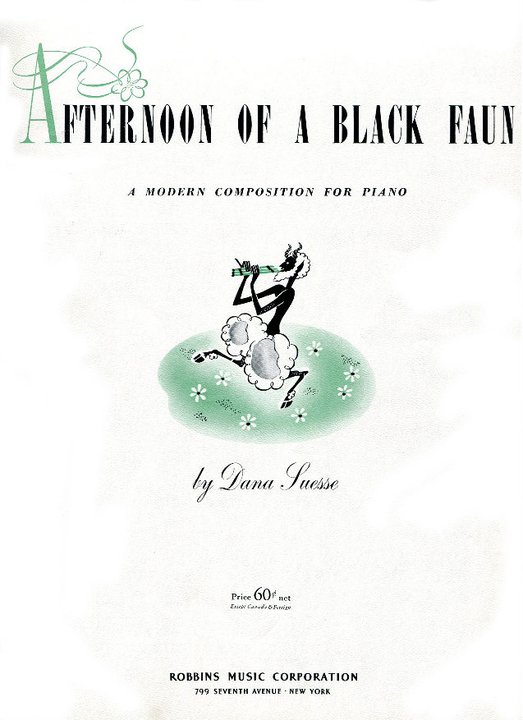

Somehow during Casa Mañana, Dana found time to compose an instrumental called Evening In Harlem. In July 1936 Adolph Deutsch (who had previously orchestrated Suesse’s Blue Moonlight) orchestrated it for Paul Whiteman’s 24-piece orchestra, including three pianos, one of which was the featured solo piano. The composition would eventually be called Afternoon Of A Black Faun.

In the spring of 1937, fresh off the triumph of the Fort Worth Frontier Fiesta, Billy Rose and his team – including Dana – were off to the Lake Erie waterfront to stage the Cleveland Exposition Aquacade, another extravaganza featuring 160-foot-wide floating stage, 21 tons of electrical equipment, a multicolored water screen, more revolving stages, chromium staircases and 3 million gallons of water for an audience of 5,000. Led by the show’s stars, Olympic diving champions Johnnie Weismuller and Eleanor Holm, a hundred “Aquabelles” (in Rose’s vernacular) grit their teeth while doing backstroke ballet in the frigid waters of the lake. Two years later, they would repeat their Aquacade feat at the 9,000-seat Flushing Meadows amphitheater for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York.

Meanwhile, Amon Carter sent Rose, Dana and Frontier Fiesta star Everett Marshall to the White House where they dined and entertained the Roosevelts and their guests with songs from the three Centennial Fiesta shows. On June 12, 1937 – a day after departing Fort Worth – Dana wired her mother: “Just arrived in Washington. Dining with President tomorrow night. Love, Dana.” Her memories of Fort Worth and D.C. would stay with her the rest of her life. A month later – on July 11 – the world was shocked by the news that George Gershwin had died in California at the unfair age of 37 following surgery to remove a glioblastoma.

At one of his own Carnegie Hall concerts in 1938, Ferde Grofé premiered the piece Dana had composed in Fort Worth – Evening in Harlem/Afternoon of a Black Faun. She continued composing concert music in the jazz-classical vein: Serenade for a Skyscraper (1938), a harp concerto called Young Man With a Harp (1939) that earned her another dinner invitation from the Roosevelts, a Concerto in E minor for Two Pianos (1941) and The Cocktail Suite (1941) whose four movements were impishly titled Old-Fashioned, Champagne, Bacardi and Manhattan. She enjoyed bestowing those descriptive titles ever since the Concerto in Three Rhythms, whose movements were Fox-Trot, Blues and Rag. The movements of her next serious work wouldn’t have such good-humored titles. In 1942, with the United States suddenly at war with the Axis powers, she composed an orchestral suite called Three Cities whose movements – Vienna 1938, Warsaw 1939 and Paris 1940 – were dedicated to three European capitals that had fallen to the Nazis, each in its own way. In her program note, she typed:

“Vienna died dancing… for the story goes that on the eve of the Anschluss, the Old Guard aristocracy attended one last ball – the gentlemen resplendent in their uniforms, the ladies wearing their best gowns, glittering with jewels… It was Vienna’s ‘last waltz.’ Warsaw died fighting. During the city’s long and terrible siege, the people were heartened by the music of Chopin’s famous Polonaise, played night and day on Radio Warsaw, for as long as they could hear it, they knew the city had not yet fallen. At last came silence – and surrender… Paris died betrayed from within. In that spring of 1940, life went on as usual… Children still romped in the Luxembourg Gardens, in the Bois the rich dined and danced the tango, the bal musettes were gay with cheap song. But underneath it all lay mortal grief and the bitter knowledge of that betrayal.”

Through the mid-‘40s, she wrote music for Billy Rose’s nightclub, the Diamond Horseshoe, in Manhattan’s Theater District. But she also had a touch of the theater bug, and she partnered with her friend, magazine writer Virginia Faulkner, on a musical comedy called It Takes Two. The show opened on Broadway in late January 1947 and closed before the month was out. But not before the authors were paid $50,000 by RKO for the movie rights to a film that was never made. Suddenly, Dana had the spare cash to move to Paris for three years and study with the renowned teacher of composers, Nadia Boulanger.

“Mademoiselle,” as she was called by her students, had accepted Dana on the recommendation of Robert Russell Bennett. In the States, she was famed for having mentored the deans of American Music: Aaron Copland, Roy Harris and Virgil Thomson and many others besides. She was lenient with her lesser students, strict with her best ones. “Bless her, what a tyrant she was!” Dana enthused. In a letter to her mother, she confessed, “It’s unfortunate I should have to spend all these… preliminary months learning things I should have learned twenty years ago… Heretofore, I have mostly written music by instinct and some of the things have been right. But a good many have been wrong… Native talent carries one just so far and no farther.” She was put through an intense training regimen of harmony, counterpoint and orchestration, and she was put to work composing canons, string quartets, rondos and sonatas. They worked together industriously, even on holidays.

On October 20, 1950, the SS Atlantique sailed into New York harbor with Dana aboard – three years to the day after she had begun studies with Nadia Boulanger. Now confident in herself as a fully formed musician, she came to think of her previous work – the lucrative popular songs and the novelty concert pieces such as Jazz Nocturne – in diminished light. She wanted to do bigger things and turned her attention to composing larger concert works and writing for Broadway. She landed her biggest theatrical success with the incidental music to George Axelrod’s play The Seven Year Itch, produced by her first husband Courtney Burr. The play ran for 1,141 performances from November 1952 to August 1955, making it Broadway’s longest running stage play (non-musical) of the ‘50s. But when Billy Wilder adapted it for his 1955 film with Tom Ewell reprising the lead role, the movie director turned to veteran Hollywood composer Alfred Newman for the music. Dana continued to compose for other theater projects. Two of them opened – Josephine (1953) and Come Play with Me (1959) – but their runs were brief.

On October 20, 1950, the SS Atlantique sailed into New York harbor with Dana aboard – three years to the day after she had begun studies with Nadia Boulanger. Now confident in herself as a fully formed musician, she came to think of her previous work – the lucrative popular songs and the novelty concert pieces such as Jazz Nocturne – in diminished light. She wanted to do bigger things and turned her attention to composing larger concert works and writing for Broadway. She landed her biggest theatrical success with the incidental music to George Axelrod’s play The Seven Year Itch, produced by her first husband Courtney Burr. The play ran for 1,141 performances from November 1952 to August 1955, making it Broadway’s longest running stage play (non-musical) of the ‘50s. But when Billy Wilder adapted it for his 1955 film with Tom Ewell reprising the lead role, the movie director turned to veteran Hollywood composer Alfred Newman for the music. Dana continued to compose for other theater projects. Two of them opened – Josephine (1953) and Come Play with Me (1959) – but their runs were brief.

Meanwhile, she composed more piano concertos. She premiered her Concerto Romantico with the Symphony of the Air at Cooper Union in March 1955. A year later, she gave the first performance of her Concerto in Rhythm with Frederick Fennell and the Rochester Civic Orchestra. The Rochester Times-Union said about the work, later renamed Jazz Concerto in D: “This is melodic music, full of surging pulse and vitality, fashioned as a work of art and possessing some thrilling climaxes.” Fennell – who’d written her out of the blue to suggest a collaboration – became a great friend and her staunchest booster. But it was hard to get the rest of the world interested in her concert music, and popular styles were changing. The Swing Era was over. She found progressive jazz and be-bop intriguing, and she admired the work of younger artists the likes of Cy Coleman and Billy Taylor. But when Bill Haley & His Comets played Rock Around the Clock on the Ed Sullivan Show in August 1955, and the song was featured in the film Blackboard Jungle the same year, a new era in popular music had arrived. For the first time in her life, Dana was no longer part of it.

In 1970, she moved away from Manhattan to Connecticut where she met Edwin DeLinks, whom she married the following year. She and Courtney Burr had divorced in 1954. Before retiring to the Virgin Islands, Dana and Edwin decided to use part of their savings to mount a concert retrospective of her symphonic works at Carnegie Hall. Some of her old friends helped with raising funds, among them, Eddie Heyman, Ira Gershwin, Johnny Green and Paul Whiteman’s widow, Margaret. After a year of preparation, the concert took place on December 11, 1974, under the baton of her friend Frederick Fennell. Cy Coleman performed her Concerto Romantico and Jazz Concerto, and Dana herself played The Blues movement of her Concerto in Three Rhythms. The following July, four of her works, including the newly orchestrated Serenade to a Skyscraper and 110th Street Rhumba, were presented at the Newport Music Festival on a concert program devoted to music composed by women. The Delinks decamped to St. Croix, where they enjoyed the white sand and blue sea until Edwin’s death in 1981.

Dana tried relocating to Shreveport, but the living wasn’t easy. She returned to Manhattan in 1982 where she rented a pair of adjoining rooms at the Gramercy Park Hotel. The press and public were just then re-discovering the old lions of Tin Pan Alley, and she was suddenly courted for interviews and feted at retrospective concerts. Her hometown, Kansas City, declared a Dana Suesse Day on October, 1, 1982, and awarded her the key to the city. She continued working on her stage projects to the end of her life. She was finishing up a musical version of Mr. Sycamore – the Robert Ayres short story about a man who decides to become a tree – and shopping her (non-musical) stage play Nemesis when she suffered a stroke on October 16, 1987 and died in New York City.