Fall Concert 2018

Fort Worth Civic Orchestra

Kurt Sprenger, Music Director

Featuring the Southwestern Master Chorale

Saturday, November 17 at 7:30 p.m.

Admission Free

Truett Auditorium

Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary

Concert Program

John Rutter (b. 1945)

Gloria

In a career that now spans over 50 years, the London-born composer John Rutter has firmly established himself as the preeminent writer of sacred choral works in the English-speaking world. His appealing music – often using touches of jazz and other popular styles and ranging in scale from small anthems and hymns to ambitious works like the Requiem (1985) and the Magnificat (1990) – has become essential repertoire for church choirs and choral societies everywhere.

His first major success was the Gloria, which marked his first appearance in this country. It is now one of the most frequently performed works in the choral canon. Of it, Rutter writes:

- “Gloria…was written as a concert work. It was commissioned by the Voices of Mel Olson, Omaha, Nebraska, and I directed the first performance on the occasion of my first visit to the United States in May 1974. The Latin text, drawn from the Ordinary of the Mass, is a centuries-old challenge to the composer: exalted, devotional, and jubilant by turns. My setting, which is based upon one of the Gregorian chants associated with the text, divides into three movements roughly corresponding with traditional symphonic structure. The accompaniment is for brass ensemble, with timpani, percussion, and organ – a combination which in the outer movements makes quite a joyful noise unto the Lord, but which is used more softly and introspectively in the middle movement.”

- The first movement opens with a muscular fanfare, heavy on brass and percussion, and the chorus intones Gloria in excelsis with interjecting commentary from the orchestra. The slower, middle movement was originally written with an organ prelude; in this orchestral version, its birdlike twitters are handled more colorfully by woodwinds, which set the pastoral mood for the serene choral hymn that rises in volume to a triumphal climax praising the “king of heaven” before darkening to describe the “sins of the world.” The jazzy syncopations of the final Quoniam (“For You are the only Holy One”) are a visceral, modern-day expression of joy capped by the triumphant return of the opening Gloria fanfare.

Aaron Copland (1900-1990)

Appalachian Spring

Writing in Harper’s in 1895, Dvorak predicted a distinctive American music emerging out of the popular and folk idioms of its native soil. “The people,” he wrote, “claim their own; and after all, it is for the people that we strive.” What Dvorak couldn’t have guessed was that that characteristic national voice would spring from two composers of European Jewish heritage born in Brooklyn.

George Gershwin (born 1898) expressed a music of the American city in the vibrant language of jazz. Aaron Copland’s red-blooded American sound – harder to peg but no less expressive – was more about the American heartland. His classic film scores to Of Mice and Men, Our Town and The Red Pony and his Fanfare for the Common Man celebrated the nobility of a resilient people who built a nation. But it was his three ‘frontier’ ballets – Billy the Kid, Rodeo and Appalachian Spring – that defined the new national musical language.

Copland’s ballets have parallels in the three early ‘folk’ ballets of Stravinsky, including “ritual” elements in the final ballet of each trio. But one big difference between The Rite of Spring and Appalachian Spring is that the title of Copland’s ballet is a body of water, taken from Hart Crane’s poem, The Dance:

- O Appalachian Spring! I gained the ledge;

Steep, inaccessible smile that eastward bends,

And northward reaches in that violet wedge

Of Adirondacks!

The ballet score was composed for choreographer Martha Graham, who didn’t come up with that title until the eleventh hour before its premiere at the Library of Congress in October, 1944. Graham’s concept for the ballet envisioned a 19th century Pennsylvania pioneer community coming together to erect a farmhouse for two newlyweds. Copland composed the score for 13 instruments and later, at his publisher’s suggestion, expanded it for full orchestra with about 10 minutes of cuts in the music. The original ballet score was awarded the 1945 Pulitzer Prize for Music.

The dominant sonority of the work is built on two simple augmented triads that Copland introduces in the opening bars and then superimposes to create a dense, dreamy chord of rich complexity. There are several lively dances with jagged, frequently shifting rhythms that pose challenges to dancers and musicians alike, beginning with a frisky tune for unison strings that bounces up and down the scale. The ballet’s dramatic climax comes in a set of variations on the Shaker song Simple Gifts, starting on a solo clarinet line and culminating in a heroic march for full orchestra like a noble fanfare for the common folk. The music subsides into the same gauzy haze of sound that opened the ballet.

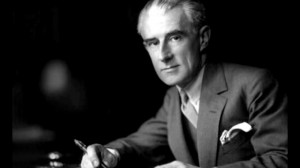

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Bolero

Just after New Year’s Day, 1928, Maurice Ravel disembarked in New York for a four-month tour of Prohibition America – provisioned with his preferred brand of Caporal cigarettes and his favorite French wines. He railroaded the length and breadth of the country, including a stop at Houston’s Rice Institute for a lecture and a pair of recitals.

Before offing to the States, he’d promised the dancer Ida Rubinstein a Spanish ballet based on Isaac Albeniz’ Iberia. On returning to France, he found that the rights to the suite were assigned to another composer, and Ravel – a notorious plodder who only averaged about one new composition a year – had just five months to deliver a ballet. One morning while summering near his boyhood home on the Basque coast – before going out for a swim – he tapped out a poky little tune on the piano with one finger and remarked to a houseguest, “Don’t you think this theme has an insistent quality? I’m going to try repeating it a number of times without any development, gradually increasing the orchestra as best I can.”

By August, he was at work on his new Fandango, though by October, he’d renamed it Bolero, and the Rubinstein troupe danced the premiere in Paris on November 22. It was as a concert piece that Bolero really caught the public’s ear, famously in a series of performances – by Arturo Toscanini and the New York Philharmonic on their European tour in 1930 – that piqued the composer’s ire. “Toscanini was taking a ridiculous tempo in the Bolero,” said Ravel, “and [I told him so], which disconcerted everyone beginning with the great virtuoso himself.” He later tried to patch things up, writing to the Italian conductor, “My dear friend, I have recently learned that there was a Toscanini-Ravel ‘affaire.’ You were probably unaware of it yourself even though I have been assured that it was mentioned in the newspapers… I trust that such news will not have altered your confidence in the admiration and the profound friendship of your Maurice Ravel.”

The work begins with a quiet, persistent beat tapped out by the drum (4,037 strokes, to be precise). Ravel, who loved mechanical gadgets, told London’s Evening Standard that the rhythm was inspired by his visit to a factory. A solo flute intones the familiar tune like a Spanish boy whistling down the street. It’s soon taken up by a parade of soloists and instrument groups – clarinets, bassoon, saxes, trombone, horn and piccolos (oftentimes well outside the comfort zone of their normal registers) – cutting a wide spectrum of orchestral color. There are 19 variations in all, gradually building in sound and fullness and culminating in a big orchestral tutti that ends the piece in a splash of noise.