Spring Concert

featuring Madison Hardick, flute

First Place, 2017 Young Musicians’ Concerto Competition

Saturday, May 6 at 7:30 p.m.

Admission Free

Truett Auditorium

Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary

2001 West Seminary Drive, Fort Worth, TX

Concert Program

J. Russell Powell

Fanfare for New Beginnings

“Fanfare for New Beginnings” was composed for the Fort Worth Civic Orchestra in February of 2017, but the germs of the main themes were born in the spring of 2016. I had recently met the woman who is now my fiancé, and obviously my new sunnier outlook on life came out in the writing of those themes. They are, in turns, bombastic and contemplative yet exuberant throughout. Tonally, the piece shifts between tertian (based on intervals of a third) and quartal (based on intervals of a fourth) harmonies. I titled the piece at its completion as a summation of its tone and of my feelings as I anticipated proposing to the woman I love. Thus, this piece is dedicated to Madysen Stewart for the love and encouragement she has provided throughout its composition.

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869)

March to the Scaffold from Symphonie Fantastique

Music’s great hallucinogenic symphony emerged from that early Romantic fog of the 1820s to ’30s that also produced the opium-tinged literary work of Coleridge, Keats, DeQuincey, Shelley and Byron. Yet while Hector Berlioz was a known user (the opiate laudanum was the aspirin of its time), the Symphonie Fantastique was inspired by his delirious infatuation with Irish actress Harriet Constance Smithson. Smitten by her portrayal of mad Ophelia in an 1827 touring production of Hamlet in Paris, he stalked her relentlessly, wrote her overflowing love letters and alarmed the woman to sheer panic.

She returned to England, he went on to Rome, but she never left his mind – and in 1830, he conceived and composed his sprawling dramatic symphony depicting episodes in the life of a tormented artist and his muse, represented by a melody he called an idée fixe. Smithson attended a performance of both the Symphonie and its sequel – Lélio, the Return to Life – in 1832, was seduced by Berlioz’ genius and finally succumbed to his flattery. Despite his inability to speak English and hers to speak French, they were inexplicably married in 1833, though in time, the marriage soured over hot tempers, infidelity and jealousy, and Smithson left him. Despite his taking a lover, Marie Recio, Berlioz provided for Smithson’s finances to the end of her life – and she, Recio and Berlioz lie together in the Montmartre Cemetery in Paris. Besides Berlioz’ Symphonie, Smithson inspired his Nine Irish Songs, La Mort d’Ophélie and Romeo et Juliette. Upon her death in 1854, Liszt wrote to Berlioz, “She inspired you, you loved her, you sung of her, her task was complete.”

The music of the fourth movement – The March to the Scaffold – was lifted from Berlioz’ unfinished opera Les Francs Juges and made a powerful impression on early audiences. The composer described the action of his roman à bass clef as follows:

“Convinced that his love is spurned, the artist poisons himself with opium. The dose of narcotic, while too weak to cause his death, plunges him into a heavy sleep accompanied by the strangest of visions. He dreams that he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned, led to the scaffold and is witnessing his own execution. The procession advances to the sound of a march that is sometimes sombre and wild, and sometimes brilliant and solemn, in which a dull sound of heavy footsteps follows without transition the loudest outbursts. At the end of the march, the first four bars of the idée fixe reappear like a final thought of love interrupted by the fatal blow.”

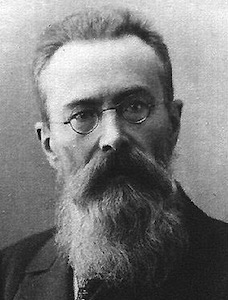

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908)

Capriccio Espagnol

Composed in 1887, “Capriccio Espagnol” was inspired by a shore leave in Spain when Rimsky-Korsakov was a young naval officer 25 years earlier. In Russian, the work is officially called “Capriccio on Spanish Themes” but may have gotten its Western title by similarity to Tchaikovsky’s picturesque travelogue, “Capriccio Italien.” The work is in five sections beginning with a lively Asturian dawn song or “Alborada.” The “Variazioni” introduces a sleepy melody for solo horn, which is passed to other instruments and sections of the orchestra in a series of variations. The third section returns to the original “Alborada” with different instrumentation and key. A mighty brass fanfare announces the “Scene and Gypsy Song,” which continues with cadenzas for solo violin, flute, clarinet and harp before launching into a lively dance in 6/8 time marked “feroce.” The string writing is still remarkable for its guitarlike strumming and spiccato (bow skittering) flourishes. The music segues without pause into the final “Asturian Fandango,” a flirtatious courtship dance in 3/4 time. The Gypsy music reappears briefly before the Capriccio ends with a dizzying coda on the original “Alborada” theme.

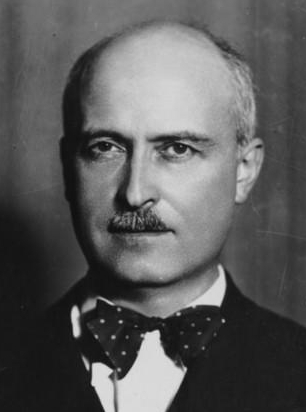

Jacques Ibert (1890-1962)

Concerto pour Flûte et Orchestre

Madison Hardick, soloist

Ibert secured a place in the musical literature for his 1922 suite “Escales” (Ports O’Call) – another work (like Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Capriccio Espagnol”) inspired by the composer’s naval service in the Mediterranean. But its popularity came to annoy Ibert, who groused that, of all his many compositions, “the only piece of mine they want to hear is ‘Escales.’”

He was a distant cousin of Manuel de Falla, but his musical family is harder to pin down. If “Escales” evoked picture-postcard Debussy, Ibert’s “Divertissement” was a goofy relation to Satie’s “Parade,” and his “Bacchanale” was evil twin to Khachaturian’s “Saber Dance.” He wrote in every genre from symphony and opera to film scores for G.W. Pabst, Orson Welles and Gene Kelly.

The Concerto was commissioned by the eminent flutist Marcel Moyse (mo-EEZ) on joining the faculty of the Paris Conservatory in 1932, and Ibert composed it over the next year. A work of sunny disposition, its two restless outer movements are naturally fluid while the central movement is built on a simple, placid melody. The suavely jazzy finale – a near-perpetual motion of flowing triplets interrupted by syncopated jabs from the orchestra – soon became a mandatory audition piece at the Conservatoire for its smooth virtuosity.

Jon Fortman (b. 1961)

A Hymn for Christopher Comer

“A Hymn for Christopher Comer” was submitted as one of many elements of Fortman’s final Capstone Project completed in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Liberal Studies at Southern Methodist University, which he received in 2016. In this project titled, “Daddy What Are Shadows Made Of?: Questions and Aspects of Childhood in Music Composition, Poetry, and Literature,” Fortman’s piece was included as an example of musical composition created in regard/response to the unfortunate aspect of childhood, that of death. Christopher Comer was a childhood friend of Fortman’s who died of heart failure at the age of seven in 1971.

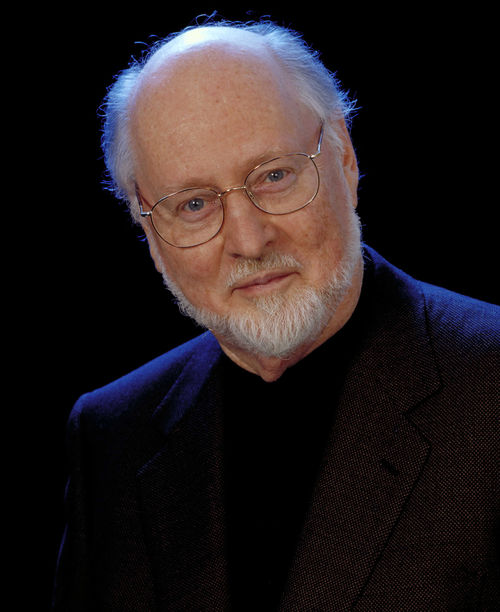

John Williams (b. 1932)

Summon the Heroes

Long considered Hollywood’s most celebrated and best known film composer (his 50 Academy Award nominations put him second in line to Walt Disney), Williams is also the composer of music for no fewer than four Olympic Games. His first, the brass-heavy “Olympic Fanfare and Theme” for the Los Angeles Summer Games (1984) was immediately followed by “The Olympic Spirit” for the Seoul Games (1988). He also composed “Call of the Champions” for the 2002 Winter Games in Salt Lake City. “Summon the Heroes” was written for the Centennial of the Modern Olympic Games held in Atlanta (1996) and is familiar from its overuse by NBC Sports’ broadcast intros and outros. If Williams the film composer has been known to mine the classical repertoire for his inspiration, Williams the Olympian composer here pushes strong emotional buttons with brass, drums and major triads that might remind a listener of Aaron Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man.” The composer has said that his music was inspired by the photograph of a female athlete in mid-air, “…every fiber of her being stretching for a ball just beyond her reach.”