Winter Concert

Fort Worth Civic Orchestra

Kurt Sprenger, Music Director

Swang Lin, Violin Soloist*

Saturday, March 3 at 7:30 p.m.

Truett Auditorium

Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary

2001 West Seminary Drive, Fort Worth, TX

Admission Free

Swang Lin joined the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra in 1991 and was soon appointed associate concertmaster, serving as acting concertmaster from 1998 to 2001. Before joining the FWSO, he performed with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra and the Orchestra of St. Luke’s in New York and in concert halls across the United States and Europe, including Royal Albert Hall, Carnegie Hall, Avery Fisher Hall, and the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. He has held concertmaster positions with the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra, Taipei City Symphony Orchestra, and Bear Valley Festival Orchestra. He also has served as a faculty member and performing artist for festivals including Tanglewood, Caramoor, Colorado, Utah, and BBC Proms.

A frequent soloist with the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, Swang has also soloed with the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra, Kaohsiung City Symphony Orchestra (Taiwan), Shanghai Broadcast Symphony Orchestra, Kunming Symphony (China), and Taipei City Symphony Orchestra, among other ensembles. His performances have been heard on National Public Radio’s Performance Today program and broadcast on Good Morning America and on public television.

An active proponent of chamber music, he has performed with the Fine Arts Chamber Players of Dallas, Chamber Music Society of Fort Worth, Spectrum Chamber Music Society, Basically Beethoven, and Snowbird Institute String Chamber Music Festival, and participated in several faculty concerts at TCU.

A native of Taipei, Taiwan, Swang began studying the violin at age six. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in violin performance from the Eastman School of Music under the instruction of Zvi Zeiltin. His other teachers include Naoko Tanaka, Chong-Ping Hsieh, and Hsing-Cheng Si-Tu. Swang resides in Euless with his lovely wife, Amy, and their two cats, Misha and Pinky. He plays the “Eugenie, ex-Mackenzie” Antonio Stradivari violin (1685), generously on loan to the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra Association from an anonymous local patron.

Concert Program

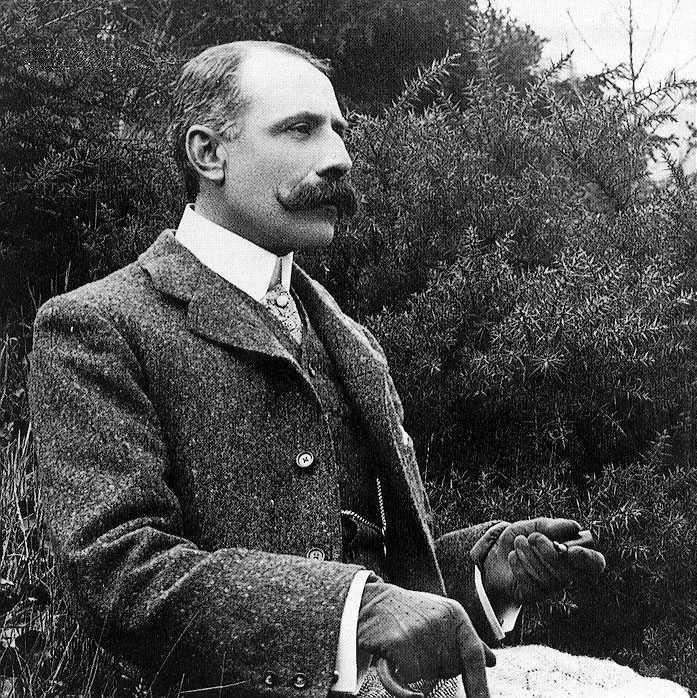

Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 in D, Op. 39

The name of Elgar’s marches, whose stately comportment is Englishness distilled, comes from the pivotal scene in Act III of Shakespeare’s Othello in which the Moor renounces Desdemona and the glories of his past military victories:

O farewell,

Farewell the neighing steed, and the shrill trump,

The spirit-stirring drum, th’ ear-piercing fife;

The royal banner, and all quality,

Pride, pomp, and circumstance of glorious war!

Elgar composed the marches on commission from London publisher Boosey & Hawkes. There were to have been six in all, and the first four were composed between 1901 and 1907. The fifth march was written near the end of his life in 1930, and a sixth was elaborated from archival sketches in 2006 by Elgar scholar Anthony Payne, who had previously reconstructed Elgar’s Symphony No. 3.

The March No. 1 was premiered by conductor and cotton merchant Alfred Rodewald and the Liverpool Orchestral Society (the work’s dedicatees) on October 19, 1901. Four days later, Henry Wood (not yet Sir Henry) conducted it a London Proms concert in Queens Hall and had to repeat it twice as a “double encore” to satisfy the audience. The following year, Elgar recycled his now famous march theme as “The Land of Hope and Glory” section of his Coronation Ode for the crowning ceremony of Edward VII. Its traditional use as a graduation processional dated from 1905 when Yale University conferred an honorary doctorate on Elgar and had the New Haven Symphony perform the March No. 1 as the recessional.

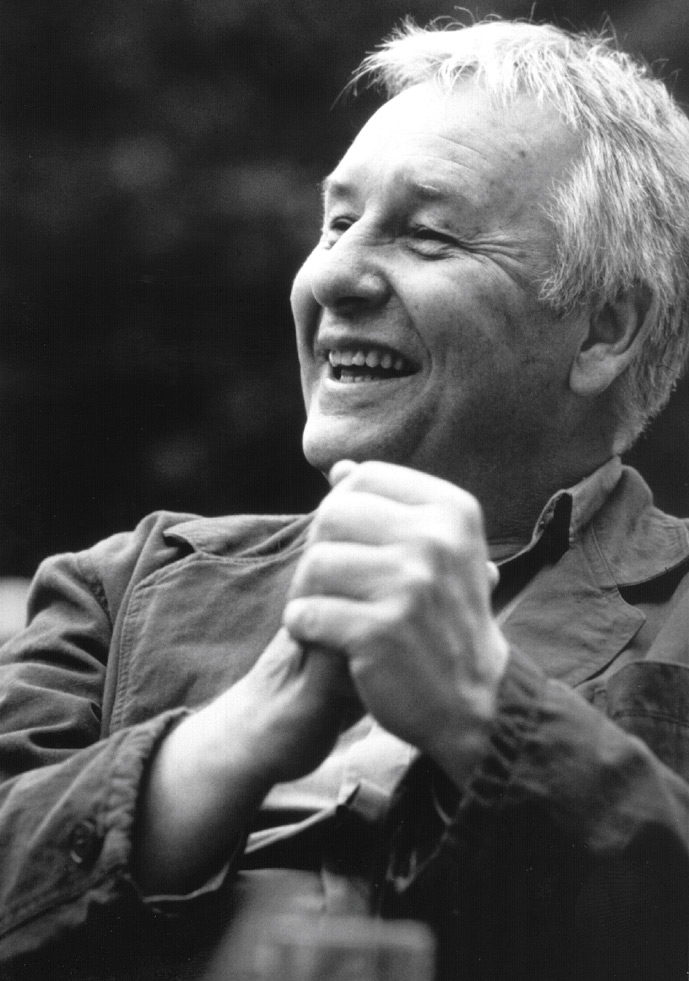

Henryk Górecki (1933-2010)

Symphony No. 4 (“Tansman Episodes”)

The reputation of the contemporary Polish composer Henryk Górecki (read: goo-RET-ski) rests almost entirely on his madly popular Symphony No. 3 (“Symphony of Sorrowful Songs”) written in 1977 — or more accurately, on its 1992 London Sinfonietta recording featuring soprano soloist Dawn Upshaw. To date, it has sold over a million copies, an improbable number for any classical release, let alone a modern work.

But the listener-friendly Third Symphony — a tunefully emotional expression of parental loss in time of war – was an outlier in Górecki’s otherwise thorny, listener-challenging output. The composer himself remarked, “I never write for my listeners… I have something to tell them, but the audience must also put a certain effort into it.” When it came time to write his Fourth Symphony near the end of his life, he reverted to old form. Górecki completed the short score (a composer’s shorthand notation) before his death, but the work of filling out the orchestration fell to his son, Mikolaj, and the symphony was premiered by the London Philharmonic in 2014.

The savage, flagrantly repetitive five-note motif with bass drum explosions that fills the first movement spells the letters of Polish composer Alexandre Tansman’s name (hence the symphony’s subtitle). But the slow movement’s theme, intoned by a pair of clarinets and muted strings, evokes music by another of Górecki’s compatriots, the Stabat Mater of Karol Szymanowski. The scherzo is a march for horns and trombones that could be mistaken for Stravinsky’s A Soldier’s Tale — with a plaintive middle trio section for piano, violin, cello and piccolo. The finale quickens the pace with a jaunty variation on the five-note opening motif, which returns in its identifiably repetitive glory wtih a finish that rolls like thunder.

Karl Goldmark (1830-1915)

Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 28*

At its American premiere in 1890, the eminent Boston critic John Sullivan Dwight wrote, “The Violin Concerto of Goldmark sins very little in the way of modern extravagances; there is nothing coarse or boisterous about it. And only occasionally, seldom in fact, does it sound far-fetched. But it is long without obvious necessity or reason.”

Karl Goldmark is a near-forgotten man today, but in his own day, the Austro-Hungarian composer’s Rustic Wedding Symphony, In Springtime overture and violin concerto were much admired and much played. Though his A minor violin concerto of 1877 preceded the Tchaikovsky and Brahms concertos by just a few months, it was closer to Vieuxtemps and Wieniawski without the ostentation. A violinist himself, Goldmark spooled out extravagantly lyrical lines with a natural facility that masked the virtuosity but tested the patience of a critic like Dwight.

A stern orchestral march and trumpet fanfare announce the soloist’s languorous cantabile. The march theme is echoed in the solo line and again in an elaborate orchestral fugato before the violin’s brief cadenza and long, inventively melodic discourse to the end of the movement. The fittingly named Air is a quiet song that suggests a sentimental Scottish ballad. A brisk polonaise introduces a finale that showcases a bag of violinistic tricks — dotted piqué (aka shoeshine) bowings, ricocheted arpeggios, a cadenza of finger-gnarling double-stops — that always play second fiddle to its melodies.