Winter Concert 2019

Delmar Pettys, Violin

Fort Worth Civic Orchestra

Kurt Sprenger, Music Director

Saturday, March 2 at 7:30 p.m.

Truett Auditorium

Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary

2001 West Seminary Drive, Fort Worth, TX

Admission Free

About Our Soloist

Delmar Pettys is much admired in North Texas, having served as principal second violin of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra from 1986-2009 as well as a soloist and ensemble leader in his concert appearances and recordings outside the DSO.

A graduate of the Juilliard School, he studied violin with Oscar Shumsky and Joseph Fuchs and chamber music with the members of the Juilliard String Quartet. Mr. Pettys was a longtime member of the Lenox String Quartet. He founded the Evansville Chamber Orchestra and served as artistic director of the Evansville Chamber Players.

He was a member of the Chicago Ensemble and played in the 1965 Casals Festival Orchestra. In leadership capacities, Mr. Pettys was concertmaster of the Evansville Philharmonic Orchestra (1977-96), acting concertmaster of the San Francisco Symphony (1976-77) and acting concertmaster of the Dallas Opera (2009-10). He was a charter member, concertmaster and frequent soloist with the Music in the Mountains Festival in Durango, Colorado. He has been concertmaster of the Eugene Oregon Opera since 2012.

Mr. Pettys has held teaching positions at Grinnell College, State University of New York at Binghamton, University of Evansville, University of North Texas, Texas Christian University and Baylor University.

Concert Program

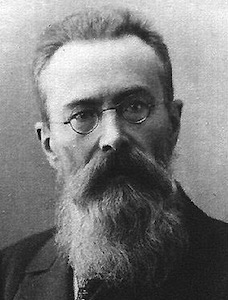

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908)

Russian Easter Overture

It was during the momentous year between December 17, 1887 and December 15, 1888, that Rimsky conducted the premieres of the three works that cemented his reputation as Russia’s preeminent national composer: Capriccio Espagnol, Scheherazade and Russian Easter Overture. The latter, officially titled Svetliy prazdnik or Bright Holiday (as Easter is called in Russia) was a musical impression of the Eastern Orthodox holiday as celebrated in the composer’s homeland. In contrast to the serenity of Western church festivities, the Russian holiday combined the solemnity of medieval canticle with ancient traditions of vernal pagan revelry. Rimsky used liturgical themes he found in a collection of Russian Orthodox chants, most prominently, the opening canticle Let God Arise alternating between woodwinds and strings with interpolated violin, flute and clarinet solos imitating spring birdsong. A solo cello intones the ecclesiastical hymn An Angel Cried Out against chirruping woodwinds, and the two melodies fill out the introduction in alternating verses until the breathless allegro agitato on the liturgical theme Let Them That Hate Him Flee. The tolling of Russian bells – so colorfully imitated in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov and The Great Gate of Kiev – is no less vivid in Rimsky’s pizzicato violins. The trumpets blast a joyous fanfare, and the noisy jubilation ends on the canticle Christ Is Arisen.

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Violin Concerto No. 2 in G minor

“We need to bring Prokofiev back home,” Stalin wrote in his diary. The composer had been granted permission to go abroad in 1918, soon after the Revolution. By 1925, though, the Soviet Union had begun courting him to return. The regime was desperate for celebrities and had reached out to Rachmaninoff and Stravinsky, both of whom had left before Prokofiev. But it was Prokofiev who seriously flirted with the idea of coming home as early as 1927.

In 1935, he and his family spent an idyllic summer on the Oka River just outside of Moscow. There, surrounded by the area’s natural beauty, Prokofiev was inspired to compose his piano score to Romeo & Juliet and work on his second violin concerto. The concerto was for French violinist Robert Soetens, who’d given the premiere (with Samuel Dushkin) of Prokofiev’s Sonata for Two Violins as well as the first performance of Ravel’s Tzigane in its violin-piano version. Stravinsky had already composed a concerto for Dushkin, and Prokofiev had decided to do likewise for Soetens.

Prokofiev worked on it at spare moments while on his concert tours and other travels. He quipped that he began the concerto in Paris, wrote the second movement in Voronezh and completed it in Baku. Soetens premiered it with Enrique Arbós and the Madrid Symphony Orchestra in December 1935 while he and Prokofiev were on a joint concert tour, and he continued to perform it until he was 95. Soetens died in 1997 at the age of 100.

The first movement has two principal melodies: an ascending motif in G minor heard at the outset in the unaccompanied violin, alternating with a contrasting downward line akin to La Vie En Rose. The second movement – whose broadly singing theme in 4/4 and clarinet/pizzicato accompaniment in 12/8 sets up a rhythmic tension of two-against-three – could easily have been a pas de deux scene from Romeo. The final allegro ben marcato is an energetic rondo – a series of episodic variations – with a recurring dance for the violin and castanets that doesn’t sound remotely Spanish.

Two months after the concerto’s premiere, Shostakovich was denounced in Pravda. And over the summer of 1936, the first show trial of the Great Purge was convened. By then, Prokofiev had finally repatriated to the Soviet Union. Given assurances of his freedom to travel, commissions, royalties and a comfortable lifestyle, he continued touring abroad until 1938 when the doors to the outside world closed on him for good. He and Stalin died on the same day, March 5, 1953.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Marche Slave

The Serbo-Turkish War of 1876 was another of those Balkan uprisings that sucked the region’s powers into a broader conflict, here, the Great Eastern Crisis in the Ottoman Empire. Russian volunteers streamed into Serbia to help their fellow Slavs while the Imperial Russian government weighed a formal declaration of war against the Turks.

Like his countrymen, Tchaikovsky was sympathetic to the Serb cause, and he immediately agreed when Nikolai Rubenstein asked him to write a short work for a concert to benefit wounded Serbian and Russian soldiers. He completed the Serbo-Russian March (as he first called it before its French title was universally accepted) in the space of five days in September 1876, and the piece was premiered in November.

The March followed a deliberately descriptive program using themes Tchaikovsky found in a published collection of Serbian folk songs. It opens with the tune he made famous, a funereal The Bright Sun Shines Not depicting the misery of the Serb people under the Turkish yoke. The mood brightens considerably with the major key entry of a patriotic song, The Serb Soldier Happily Goes to War. Tchaikovsky then invents the trick he would put to good use six years later in his overture 1812, layering ominously dark war clouds that crescendo into a fierce battle scene. Solo timpani set the march tempo for the second part, which mixes Serb and Russian themes and prophetically introduces the Russian national anthem God Save the Tsar in the thick of combat to save the day. (It was Russia’s entry into the war in 1877 that tipped the balance and led the Turks to sue for peace the following year.)

Marche Slave was a sensation at its premiere, and the composer frequently conducted it on his concert tours to end an evening with a predictably unceremonious bang.