FWCO Winter Concert

March 9, 2024 at 7:30 p.m.

Birchman Baptist Church

A La Breve

Prepare for liftoff into near Earth orbit with Michael Daugherty's percussion tour de force UFO, featuring FWCO's principal percussionist Tim Swanger as soloist.

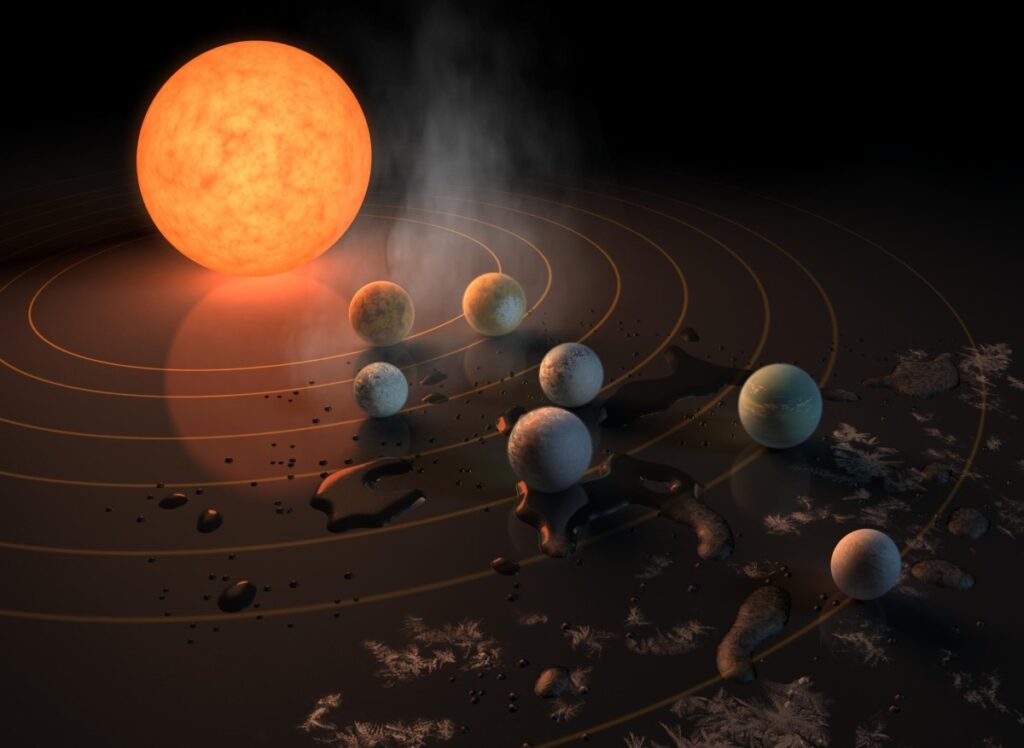

Then take a tour of the cosmos in selections from Gustav Holst's suite for large orchestra The Planets.

Works

MICHAEL DAUGHERTY – UFO

GUSTAV HOLST – Selections from THE PLANETS

Kurt Sprenger, Music Director

Fort Worth Civic Orchestra

Tim Swanger, Percussion Soloist

Program Notes

Michael Daugherty (b. 1954)

UFO

The concerto is inspired by the unidentified flying objects that have become an obsession in American popular culture. The soloist is introduced as an alien, arriving unexpectedly and playing mysterious percussion instruments in unfamiliar ways. The three major sections of the composition are entitled “Unidentified,” “Flying,” and “Objects.” There are also two brief interludes entitled “Traveling Music” and “???” during which the percussion soloist moves through the audience and around the stage while performing sleight-of-hand improvisations that may leave the listener wondering: is this another UFO sighting?

The five movements are as follows:

I. TRAVELING MUSIC

Soloist performs on a waterphone and mechanical siren, with strings.

II. UNIDENTIFIED

Soloist performs on xylophone, ice cymbal, crasher, slasher, brake drum, spring (or other “trash” instruments), earth plate, cymbal disc, and Chinese gong, with full orchestra.

In July 1947 near Roswell, New Mexico, a rancher heard a loud explosion and discovered strange metal scraps in the desert. Responding to national newspaper reports of this “UFO crash,” government agencies quickly converged on the wreckage site and confiscated the evidence. The “incident at Roswell” resonates in the popular imagination because to this day the government file remains top secret. What happened to those scattered metal scraps? They resonate on the concert stage, as the percussionist plays on xylophone and eight pieces of unidentified metal.

III. FLYING

Soloist performs on vibraphone, 3 cymbals, and Mark tree, with full orchestra.

An airplane pilot flying near Mount Rainier, Washington, spotted a formation of bright objects which he described as “flying saucers,” traveling at incredible speed through the sky. This 1947 sighting made international headlines and launched the modern UFO craze, with the proliferation of UFO magazines, clubs, conferences, photographs and films. In this movement we hear an alternation between slow and fast sections. A mysterious melody, introduced by the vibraphone, is echoed kaleidoscopically like a halo of sound throughout the orchestra. Periodically this slow motion music accelerates into fugues flying at supersonic tempos. The solo percussionist gives a virtuoso performance on vibraphone, Mark tree, and cymbals that hover and shimmer in the air like flying saucers.

IV. ???

Soloist performs on non-pitched “alien” instruments, with contrabassoon and optional percussion performers placed in the performance space, in order to create a surround-sound effect.

V. OBJECTS

Soloist performs on 5 tom-toms, 8 octobans, bongos, kit bass drum, alien cymbal, 3 small cymbals, various metal objects, 3 temple blocks, 3 Latin cowbells, mechanical siren, and waterphone, with full orchestra. Pulsating with rhythms in 5/4 time, this section features percussion instruments that suggest the outer trappings and inner machinery of a fine-tuned alien aircraft.

–Michael Daugherty

Gustav Holst (1874-1934)

The Planets, Op. 32

Gustav Mahler may have been a man of agonies and ecstasies, but Gustav Holst was the more interesting guy to know. An inquisitive man of the world, a socialist in the Pre-Raphaelite mold of William Morris, a firm agnostic with a magnetic attraction to religion and a creative teacher at a school for girls, he physically resembled Clark Kent but composed like Superman. Holst played for British troops in Salonika and Constantinople during The Great War. He taught himself Sanskrit to translate the Rig Vedas and Mahabharata into choral and operatic works. His musical fascination with the world’s religions - spanning Christianity (his cantata Hymn of Jesus), Hinduism (the opera Savitri) and the gods of the Roman pantheon (The Planets) - seemed dedicated to the proposition that all religions are created equal.

Holst was nearing 40 in 1913 and feeling dispirited over his inability to make a living as a composer (“I’m fed up with music, especially my own”). To cheer him up, his friend, the author Clifford Bax invited him along on a tour of Spain and Majorca with his brother, composer Arnold Bax, and music patron Henry Balfour Gardiner. Holst was a sullen companion, often striking out on his own apart from the others, but he took an interest in an astrology book that Clifford had brought along and began to ponder the musical and mythical identities of the seven known extraterrestrial planets (Pluto the dwarf planet wasn’t revealed until 1930). In 1914 – with eerie prescience – he began sketching Mars, the Bringer of War just weeks before Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination and finished laying it out during a bucolic summer cottage stay as the guns of August roared toward Tannenberg and the Marne. He completed the rest of the suite over the next two years – a pet project unhurried by commission or performance prospects. The war made it nearly impossible to assemble the extravagant forces called for in his “suite for large orchestra.” Its first performance was a private concert organized by Gardiner for 250 guests on September 29, 1918 as a gift to Holst. The giddy composer told Adrian Boult, “[he] has given me a wonderful parting present... Queen’s Hall, full of the Queen’s Hall Orchestra, for the whole morning of Sunday week. We’re going to do The Planets, and you’re going to conduct!” The first complete public performance on November 15, 1920 was a seismic event that catapulted Holst into the first rank of English composers, though he never again attempted anything as audacious or sweeping in scope – and The Planets has been a favorite of audiences for a century.