May 11, 2024 at 7:30 p.m.

Birchman Baptist Church

A La Breve

The concert opens with a new fanfare by Montana composer Donald O. Johnston and the exotic exuberance of the Danse Bacchanal from by Saint-Saëns’ opera Samson et Dalila. We also proudly showcase the co-winners of FWCO’s annual Young Artists Competition, violinist Karina Foster and pianist Alex Marquez.

Program Notes

Donald O. Johnston (b. 1929)

Fanfare in Memoriam (from The Lewis and Clark Symphony)

Donald Johnston studied at Macalester College (St. Paul, Minnesota) and Northwestern University in addition to studies with composers Bernard Rogers and Howard Hanson at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. He has composed numerous choral and orchestral works (including six symphonies), an opera, chamber music and works for band. In his music, he aims to validate the neo-Romantic tradition of his mentor, Howard Hanson with “logical, well-balanced formal construction; piquant harmonies; striking rhythmic constructions — all of these have an immediate appeal for audiences.”

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921)

Danse Bacchanal (from Samson et Dalila)

Like Handel before him, Camille Saint-Saëns saw great dramatic possibilities in the story of Samson and Delilah. With its intense themes of tribal allegiance, romantic desire, betrayal, humiliation and revenge, it was operatic gold. Yet despite the rich vein of human vice and frailty to be mined from the Old Testament – and despite the composer’s growing reputation – Paris’ opera houses feared that their patrons would stay away en masse from a show based on a Biblical subject and refused to mount his opera.

Like Handel before him, Camille Saint-Saëns saw great dramatic possibilities in the story of Samson and Delilah. With its intense themes of tribal allegiance, romantic desire, betrayal, humiliation and revenge, it was operatic gold. Yet despite the rich vein of human vice and frailty to be mined from the Old Testament – and despite the composer’s growing reputation – Paris’ opera houses feared that their patrons would stay away en masse from a show based on a Biblical subject and refused to mount his opera.

Riding to Saint-Saëns’ rescue was composer, pianist and priest Franz Liszt, who took on the project and conducted the concert premiere of Samson et Dalila in Weimar in December, 1877. It would be another 15 years before opera finally came to Paris for its stage premiere, but the choice of subject matter would prove to be wise. Of the 13 operas that Saint-Saëns wrote, only Samson has found a welcome home in the world’s opera houses.

A popular concert piece, the exuberant Danse Bacchanale is from the ballet music in Act III. The Philistines celebrate their deliverance from Samson in a wild, orgiastic dance before the disgraced hero – blind and shackled – is dragged to the Temple of Dagon for his final denouement.

Saint-Saëns traveled widely, and his music sometimes reflected exotic locales in Africa and the Middle East – his Suite Algérienne and Egyptian Concerto, for instance. Though the ancient Palestine of Biblical times predated the birth of Islam and the Arab golden age by two millennia, Saint-Saëns nevertheless wove Arabic-inspired melody, harmony and rhythm into the Bacchanale, starting with a sinuously lyrical oboe solo – sounding much like a muezzin’s morning prayer – to the irregular beat of the thundering timpani.

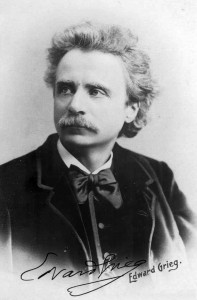

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907)

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16

It has the most iconic piano entrance in the entire concerto literature. Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto may be more heroic, Rachmaninoff’s Second more brooding, but the tumbling cascade of notes that announce the Grieg Piano Concerto is unchallenged for sheer drama.

It has the most iconic piano entrance in the entire concerto literature. Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto may be more heroic, Rachmaninoff’s Second more brooding, but the tumbling cascade of notes that announce the Grieg Piano Concerto is unchallenged for sheer drama.

All the more remarkable, considering his inspiration was the “straight-out-of-the-gate” entrance from an earlier piano concerto in A-minor, the one by Robert Schumann. Grieg first heard it when he was a student in Leipzig, played by Schumann’s widow, Clara. The falling three-note motive (sol-ti-do) in Grieg’s dramatic opening bars is a characteristic gesture of Norwegian folksong. And like the “Clara” theme of Schumann’s concerto, which weaves through much of that composer’s music, those three notes show up in several of Grieg’s later works, notably the Lyric Suite, the Symphonic Dances and his G minor String Quartet.

By the time he composed the concerto in 1868 at the tender age of 25, Grieg was already under the spell of the late Norwegian composer Rikard Nodraak, who advocated a national music language based on native folk melodies. The concerto’s themes aren’t explicitly from folk tunes, but its powerful sense of place speaks to the pervasiveness of Norway in Grieg’s musical consciousness. And like those other Romantic piano concertos, Grieg’s melodies proved irresistible to lyricists.

The spin-off songs from Grieg’s concerto haven’t proven as indelible as Tchaikovsky’s (Tonight We Love) or Rachmaninoff’s (Full Moon and Empty Arms and Eric Carmen’s All By Myself), but the Broadway schlockmeisters Wright & Forrest set words to all of the Grieg Concerto’s tunes in their 1944 musical Song of Norway. The first movement contains two important themes. After the concerto’s dramatic opening, the woodwinds whisper the main melody in A minor, or in Wright & Forrest’s irresistibly awful lyrics:

Once long ago,

Long, long ago,

’Mid these hills dwelled a maid,

Mark you well, for the maiden’s name was Norway!

Trolls and men were entranced when Norway danced!

The piano restates the melody and plays fleet-fingered arabesques before the cellos introduce the secondary idea in C major – or in the Broadway show’s flirtatious banter by Grieg, his future wife Nina and Nordraak:

Nordraak: I’ll right the world and its wrongs if you are near me.

Nina: I’ll be near you.

Grieg: I’ll write such wonderful songs if you can hear me.

Nina: I will hear you.

Franz Liszt was entranced by the concerto’s music when he read through it, but Grieg tinkered with it to the end of his life – never on the melodies but the instrumentation. The version performed here was his final edition.

Niccolò Paganini

Violin Concerto No. 1, Op. 6

In the history of violin performance, there are two distinct eras: Before Paganini and After Paganini. As an artist, he seamlessly merged technique and personal mystique – words most often used to describe his playing were “wizardry,” “demonic” and “magnetic.” Inspired by the violinist’s electrifying virtuosity, a young Franz Liszt determined to mold himself into “the Paganini of the piano.” As for the beauty of his playing, not everyone was moved. Louis Spohr wrote, “The very thing by which he fascinates the crowd debases him to a mere charlatan and does not compensate for that in which he is utterly wanting – a grand tone, a long bow-stroke and a tasteful execution.” Heinrich Heine was more direct: “I have never heard anyone play better, or for that matter, play worse than Paganini.”

In the history of violin performance, there are two distinct eras: Before Paganini and After Paganini. As an artist, he seamlessly merged technique and personal mystique – words most often used to describe his playing were “wizardry,” “demonic” and “magnetic.” Inspired by the violinist’s electrifying virtuosity, a young Franz Liszt determined to mold himself into “the Paganini of the piano.” As for the beauty of his playing, not everyone was moved. Louis Spohr wrote, “The very thing by which he fascinates the crowd debases him to a mere charlatan and does not compensate for that in which he is utterly wanting – a grand tone, a long bow-stroke and a tasteful execution.” Heinrich Heine was more direct: “I have never heard anyone play better, or for that matter, play worse than Paganini.”

Where Paganini’s life was concerned, there was no clear line between biography and mythology. His father, an amateur mandolin player, was said to have made the boy practice mandolin from age 5 and violin from age 7 from morning to night – and to hold back his food if he didn’t play perfectly. He may have gambled away his own violin and borrowed a Stradivari from a rich collector who refused to take it back after hearing Paganini play it. He may have taken Napoleon’s sister as his lover. His finger joints may have bent sideways, enabling him to play four A’s on four different strings at the same time.

He may not have invented all the techniques we associate with him – Paganini himself admitted that “many of my most brilliant and popular effects” originated with the French-Polish violinist Auguste Duranowski – but violin players who came after him have had to master rapid-fire harmonics and double-stop harmonics, ricochet bow bouncing, left-handed pizzicato, traversing the fingerboard on a single string or playing without the two middle strings. Violinists with smaller hands, notably Pablo Sarasate and Mischa Elman, avoided his music altogether.

And he guarded his secrets jealously. Apart from the 24 Caprices, Paganini’s major works remained unpublished until years after his death. When he played his concertos on tour, the handwritten parts were delivered to orchestras just before the rehearsal and collected immediately after the concert. To make his Concerto No. 1 impossible for any other violinist to play, he wrote out the orchestral parts in the key of E-flat but played his own part in D with his strings tuned up a half-step. In modern times, the concerto is played in D Major.

This most opera buffa of concertos opens suspiciously like the overture to The Barber of Seville by Paganini’s friend Rossini; the opera premiered in Rome in 1818, the concerto in Naples the following year. At times, it could be mistaken as a concerto for cymbals and orchestra, but after a Rossinian parade of melodies, the violin enters like a diva with a fioritura display spanning four-and-a-half octaves. We can only guess what the soloist is singing about in its arias, recitatives and coloratura cadenza, but the violinistic falsettos (harmonics), vocal duets (double-stops) and bel canto stylizations would sound right at home in the warmth of the footlights.