Fort Worth Civic Orchestra

Kurt Sprenger, Music Director

Winners of the Young Musicians’ Concerto Competition:

William Leicht, piano

1st Place

Eric Rau, cello

2nd Place

Saturday, May 11 at 7:30 p.m.

Truett Auditorium

Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary

2001 West Seminary Drive, Fort Worth, TX

Admission Free

#womencompose

In our 42-year history, the Fort Worth Civic Orchestra has never performed (to the best of our knowledge) any musical works composed by a woman. That realization took us by surprise, considering the fact that FWCO plays a LOT of contemporary music, a stream where women are very well represented.

So, just in time to observe 100 years since passage of the 19th Amendment that gave women the right to vote (June 4, 1919), we end our season on a splashy note with a concert featuring works by important women composers. In keeping with our mission to present music of quality to the community and to broaden our audience’s exposure to the classical literature, we add three new (to us) composers to our repertoire.

Joan Tower (b. 1938)

Fanfare No. 6 for the Uncommon Woman

Joan Tower comes from a generation of American composers who emerged in the 1970s and ‘80s, among them Philip Glass, John Corigliano, William Bolcom and Steve Reich. Though their styles ranged broadly – some were called “minimalists,” others “new Romantics” – their music embraced tonal centers, consonant harmonies and recognizable melodic themes without fear or shame. Following the experimentalism of the ‘50s and ‘60s, they reaffirmed a musical language that echoed the expressive lyricism of 19th century models but were filtered through a modern esthetic.

Tower’s standing in the musical world was firmly established with Sequoia in 1981, and in the decades since, she’s produced a much-admired body of work. She was the first woman to win the prestigious Grawemeyer Award for Music (for Silver Ladders in 1990), and her Concerto for Orchestra (1991) and Made in America (2004) have become firmly established in the repertoire.

In 1986, the Houston Symphony commissioned fanfares from 21 composers to observe the 150th year since Texas declared independence. Though it should have produced many forgettable throwaways, the project yielded notable works, including John Williams’ Celebration Fanfare, John Adams’ Tromba Lontana and Tobias Picker’s Old and Lost Rivers. The most enduring, however, has been Tower’s Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman, whose title is a play on Aaron Copland’s anthemic Fanfare for the Common Man. In the years since, she’s composed five more, dedicated as a group to “women who take risks and are adventurous.” Fanfare No. 6, composed in 2014 for piano and later arranged for full orchestra, is an energetic work of pulsating rhythms, shimmering surfaces and big, jazzy interjections. The Fanfare was premiered by Marin Alsop and the Baltimore Symphony in 2016.

In a 1991 essay about her composer residency with the St. Louis Symphony, Tower wrote: “I recently asked a pre-concert audience of around 1,500 people how many of them expected to dislike my piece, and about 90 percent of the hands went up. I then asked them how many thought that was unfair. The same hands went up! With orchestra players it’s a little better, but not much.” The League of American Orchestras has announced that it will award its Gold Baton to Joan Tower at its annual convention this June in Nashville.

Aaron Copland (1900-1990)

Fanfare for the Common Man

Copland’s fanfare was a commission from the Cincinnati Symphony, whose English music director Eugene Goosens had buoyed British public morale in the first world war with fanfares written by British composers. With the world at war again, he now invited 17 Americans (and himself) to contribute fanfares reflecting on aspects of the war, each to be unveiled weekly through the 1942-43 season. There were fanfares …for the Fighting French (Walter Piston), …for Freedom (Morton Gould), …for the Signal Corps (Howard Hanson), but Copland’s is the one that has stayed with us through the years.

Its name was inspired by Vice President Henry Wallace’s speech to the Free World Society in 1942 proclaiming “the century of the common man.” Goosens said to Copland: “Its title is as interesting as the music, and I think it is so telling that it deserves a special occasion for its performance. If it is agreeable to you, we will premiere it on March 12, 1943 at income tax time.” As Copland observed later, “I was all for honoring the common man at income tax time.”

The opening fanfare in Richard Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra (familiar as the theme to “2001: A Space Odyssey”) was built on three ascending notes (do-sol-do) in the trumpets that pose Nietzsche’s “world riddle.” Like a magician, Copland took those rising fifth and fourth intervals but started on the fifth degree of the scale (sol-do-sol) to transform Strauss’ fanfare to the Super Man – this, just as America’s fight against the Nazi war machine was beginning – into a resounding assertion of the spirit of the Common Man.

Grażyna Bacewicz (1909-1969)

Symphony No. 3

In Poland, they pronounce her name gra-ZHEE-na bot-SAY-vitch. She was a gifted violinist, composed seven violin concertos and couldn’t have escaped a life in music if she’d wanted. Her father was a choirmaster. Her brother was a composer. Her other brother was a pianist. Yet hers is the name found in the standard music histories and biographies.

Her father, Vincas Bacevičius, went by his Lithuanian name, but Grażyna identified more with her mother’s Polish nationality. After graduating from the Warsaw Conservatory in 1932, she sought the help of Nadia Boulanger in Paris to hone her composing craft just as Aaron Copland had done a decade earlier. As a violinist, Bacewicz was concertmaster of the Polish Radio Symphony until its disbanding at the outbreak of World War II, but she continued composing and giving concerts in Warsaw throughout the war. In 1945, she took a professorship at the State Conservatory of Music in Łódź. A serious auto accident in 1954 put her in the hospital with a broken pelvis, broken ribs and injuries to her head and face. A friend reported that “she was in a darkened hospital ward fighting for her life, and though she had difficulty talking, she spent the time joking and refusing to discuss the accident or the seriousness of her condition.”

By that time, Bacewicz had already begun to curtail her performing career in order to concentrate on composing; she made a complete break with the violin the year after her accident. By then, she had composed all four of her numbered symphonies, including the Third, which dates from 1952. The works she wrote in the 1940s and ‘50s are often described as neoclassical, though she disputed the term. She did, however, admit to the primacy of structure in her works. “I mainly care about the form in my compositions… [I]f you place things randomly or throw rocks on a pile, that pile will always collapse. In music, there must be rules of construction that will allow the work to stand on its feet.”

Bacewicz’ Third is in the mold of a classical four-movement symphony. The intensity of the opening Drammatico molto lives up to its name and could automatically trigger an, “Uh, oh! An ugly piece of modern music!” reaction. But a minute in, she quickens the pace and tosses a punchy rhythm around the orchestra very much like the motto of Beethoven’s Fifth, this followed by a less urgent but still dark second subject based on the introduction. A muscular development, recap and coda complete the movement’s sonata-allegro structure. The slow movement begins and ends on a stealthy bass pizzicato that bookends a luxuriantly dreamy piece of orchestral writing. The third movement is a quicksilver scherzo with prankish humor while the finale has echoes of the first movement, a slow and sinister prologue and music of obsessively pounding agitation and fury.

Watch Grażyna Bacewicz perform her own Oberek in 1952, the same year she composed her Third Symphony…

Ethel Smyth (1858-1944)

The Wreckers Overture

The history of English opera after Handel resumes – after near silence for 150 years – with Dame Ethel Smyth. (Arthur Balfe’s 1843 Bohemian Girl didn’t exactly jumpstart the artform, and the Savoy operas of Gilbert & Sullivan aren’t exactly opera.)

Smyth, the daughter of a stern military man from Kent, shocked her family when she Brexited to Germany to study music. On the continent, she hobnobbed with Clara Schumann, Brahms, Grieg, Tchaikovsky and Dvořák. She composed a large body of chamber music in the 1880s, but like her musical heroes Wagner and Berlioz, Smyth dreamed of writing opera. Her concert overture Antony and Cleopatra (1890) and choral Mass in D after Thomas à Kempis (1891) gave her a dry run managing large orchestral and vocal forces, and in 1892, she started work on both the comic opera Fantasio and her pirate opera The Wreckers.

It was on a visit to Cornwall in 1886 that Smyth first heard century-old tales of coastal villagers who doused the harbor lights to lure passing cargo ships aground on the rocks, murder the crews and plunder the ships’ stores. Sixty years before Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes, Smyth saw the possibilities of the sea as a darkly dramatic setting for opera. The Wreckers overture opens abruptly on a swashbuckling call to arms that the villagers sing in Act 1:

Haste to the shore, the storm is nigh,

The breakers roar, the seabirds cry!

Wreckers away, and haste ye!

This is followed by the heroic theme of Mark and Thirza, young lovers condemned to die in a cave amid rising tide waters for the crime of warning away the sailing ships. A liturgical chorale evokes the piety of the villagers, who credit Providence with delivering the ships, and the overture ends with a coda based on the opening chorus.

The Wreckers had only one performance at its 1906 Leipzig premiere because Smyth withdrew it over her objections to the conductor’s edits. It was mounted in London under Arthur Nikisch in 1908, under a young (not yet Sir) Thomas Beecham in 1909 and at Covent Garden in 1910 under Bruno Walter. Smyth’s Der Wald was the first opera by a woman staged at New York’s Metropolitan Opera in 1903 (followed by Kajia Saariaho’s L’Amour de loin 113 years after!).

Inspired by Emmeline Pankhurst’s campaign to win voting rights for British women, Smyth became a suffrage activist – famously serving two months in Holloway Prison with a hundred other women for a window-breaking rampage. Dame Ethel was awarded the DBE in 1922, having confessed to her diary when she was 9 of wanting “to be made a Peeress in my own right because of music.” She accepted it enthusiastically, she said, “especially as it was all due to an absurd row in the Woking Golf Club.”

Hear Dame Ethel Smyth’s recollections of Johannes Brahms…

Young Musicians’ Concerto Competition Winners

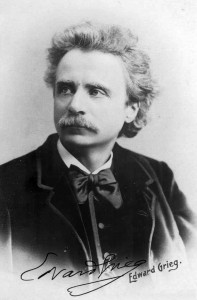

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907)

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16

William Leicht, soloist

It has the most iconic piano entrance in the entire concerto literature. Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto may be more heroic, Rachmaninoff’s Second more brooding, but the tumbling cascade of notes that announce the Grieg Piano Concerto is unchallenged for sheer drama.

All the more remarkable, considering his inspiration was the “straight-out-of-the-gate” entrance from an earlier piano concerto in A-minor, the one by Robert Schumann. Grieg first heard it when he was a student in Leipzig, played by Schumann’s widow, Clara. The falling three-note motive (sol-ti-do) in Grieg’s dramatic opening bars is a characteristic gesture of Norwegian folksong. And like the “Clara” theme of Schumann’s concerto, which weaves through much of his music, it shows up in several of Grieg’s later works, notably the Lyric Suite, the Symphonic Dances and his G minor String Quartet.

By the time he composed the concerto in 1868 at the tender age of 25, Grieg was already under the spell of the late Norwegian composer Rikard Nodraak, who advocated for a strong national music language based on native folk melodies. The concerto’s themes aren’t explicitly from folk tunes, but its powerful sense of place says something about the pervasiveness of Norway in Grieg’s musical foundation. And like the other Romantic piano concertos that joined the hit parade, his melodies proved irresistible to lyricists.

The spin-off songs from Grieg’s concerto haven’t proven as indelible as Tchaikovsky’s (“Tonight We Love”) or Rachmaninoff’s (“Full Moon and Empty Arms” and Eric Carmen’s “All By Myself”), but the Broadway schlockmeisters Wright & Forrest set words to all of the Grieg Concerto’s tunes in their 1944 musical “Song of Norway.” The first movement contains two important themes. After the concerto’s dramatic opening, the woodwinds whisper the main melody in A minor, or in Wright & Forrest’s irresistibly awful lyrics:

Once long ago,

Long, long ago,

’Mid these hills dwelled a maid,

Mark you well, for the maiden’s name was Norway!

Trolls and men were entranced when Norway danced!

The piano restates the melody and plays fleet-fingered arabesques before the cellos introduce the secondary idea in C major – or in the Broadway show’s flirtatious banter by Grieg, his future wife Nina and Nordraak:

Nordraak: I’ll right the world and its wrongs if you are near me.

Nina: I’ll be near you.

Grieg: I’ll write such wonderful songs if you can hear me.

Nina: I will hear you.

Franz Liszt was entranced by the concerto when he read through it, but Grieg tinkered with it to the end of his life – never on the melodies but the instrumentation. The version heard in this performance was his final edition.

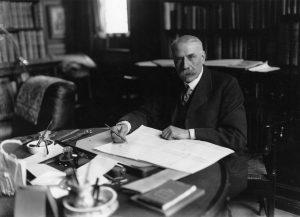

Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

Concerto in E minor for Violoncello and Orchestra, Op. 85

Eric Rau, soloist

Though he lived to the age of 77, Sir Edward Elgar’s most fruitful years were the 20 between the initial success of his “Enigma Variations” of 1899 and his Cello Concerto of 1919. Lady Elgar, who was the driving force behind his success and who never lost faith in his talents even as his own flagged, died in 1920. Without Alice, Elgar lost his will and inspiration to write. He never completed another major composition and lived out the rest of his life as a bereaved country gentleman whose quaint Edwardian era music seemed more and more out of fashion. The Cello Concerto was his final masterwork.

The apocalyptic carnage of the Great War from 1914 to 1918 had left Elgar depressed and contemplative, and he wrote little music of note during that time. But the years 1918 and 1919 brought on the final burst of creative energy that yielded his three great works in the melancholic key of E minor – the Violin Sonata, the String Quartet and the Cello Concerto. In March of 1918, Elgar checked himself into a London nursing ward for a tonsillectomy. At the time, surgery on a 61-year-old man was risky and painful, but his doctors were adamant that he have the procedure. He was weak and in pain for days afterward, but he awoke one morning and asked for a pencil and paper, on which he wrote the opening melody – a noble but forlorn theme – of the Cello Concerto.

He had no idea what to do with that little scrap of melody in 9/8 time, but he laid it aside for the better part of a year while he worked on his chamber works during the summer of 1918 in his cottage in Sussex, where he sometimes heard artillery charges from across the Channel. By May of the following year, he conceived of his 9/8 tune as the kernel for a cello concerto. Over that summer, he got up every morning at 4 or 5 to compose and score it. The work was premiered on October 27, 1919 by cellist Felix Salmond with the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Elgar. The remainder of that concert was conducted by the imperious Albert Coates, who used up so much time at the rehearsal that the orchestra had little time to prepare the concerto. Accordingly, the premiere was a disaster, and the reviews were punishing. Salmond rarely touched the piece again and did not promote it to his cello students. It was taken up by English cellist Beatrice Harrison, who made its first recordings and gave its American premiere, as well as the eminent cellist Gregor Piatigorsky. But it was the young Jacqueline du Pré whose interpretations in the ‘60s finally brought the concerto the acclaim and admiration it enjoys today.

The concerto is in four movements, though the first and last pair are played without pause like two long halves. The first opens on an anguished cadenza by the solo cello followed by the bittersweet main theme in the violas and cellos. An Elgar biographer said it was “haunted by an autumnal sadness – but the sadness of compassion, not pessimism.” The soloist gives it painful expression, and except for a lyrical but no less mournful middle section, it pervades the first movement.